His friend, fellow architect Barry Dacombe, had been inside the Christchurch city centre red zone and seen the destruction. He told Warren about the fate of the many buildings he had designed for his hometown.

“You could see the tears welling in his eyes. It was tough,’’ Dacombe said.

It must have been a particularly painful moment for a man who had dedicated his life to architecture, designing striking brutalist buildings across New Zealand and the world from the 1950s onwards. His buildings were so ubiquitous in his home town that the style of brutalist architecture he developed was simply known as the “Christchurch School”.

After the earthquakes, many of these buildings were turned to dust in a matter of months.

But there were many heroic and groundbreaking survivors from the quakes, including College House, Harewood Crematorium, the practice office in Cambridge Tce, and the Christchurch Town Hall, a masterpiece of his career that he personally fought to save from demolition after the earthquakes.

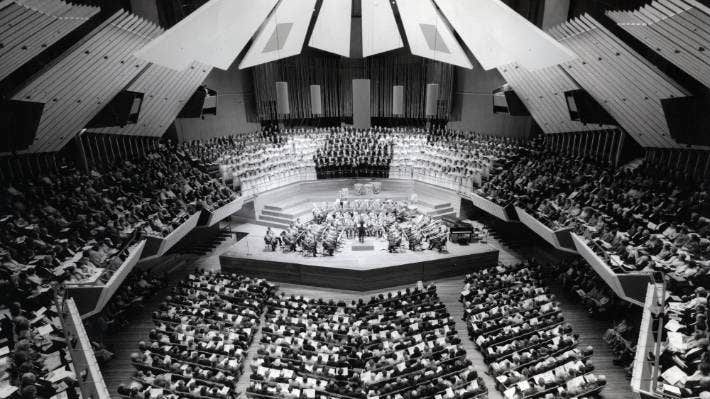

Beyond Christchurch, there were the Civic Offices in Rotorua, Television New Zealand Network Centre in Auckland and the Michael Fowler Centre in Wellington, along with projects in Washington DC, New Delhi and New York.

It was a built legacy forged by devoting almost every waking moment to architecture.

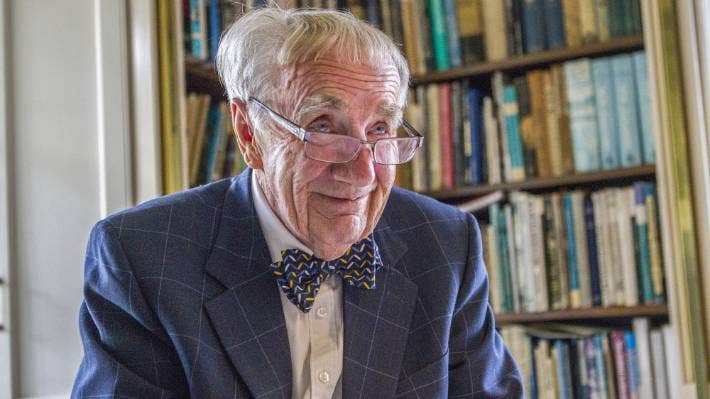

Warren, who died earlier this month at the age of 93, harnessed his intuitive design flair with his business savvy and sparkling charm to build an empire. He was always chasing what he called “the main chance” – the big commissions that allowed him to redefine post-war architecture.

But Warren would leave a powerful legacy beyond his built work. His designs would transform the face of New Zealand architecture and change the way the country thought about and experienced their built environment.

His public generosity would also leave a legacy. A trust he established In 2006 has given $2 million towards architecture education, while in 2012 he gifted his heritage home and garden outside Christchurch to the nation. He also helped protect many heritage buildings in Christchurch, including rescuing the Isaac Theatre Royal from dereliction in the 1980s.

Warren was born in Christchurch in 1929 and started working at the office of architect Cecil Wood when he was 16. He moved to England in 1953 and worked at the London County Council, where he witnessed the birth of brutalist architecture.

Warren said the partnership worked “because each of us supplied what the other lacked”. Mahoney’s daughter, Jane Mahoney, said in 2018 that the pair were “chalk and cheese”.

Warren was “the ideas man and the big-picture vision”, while Mahoney was “working through the details and turning something into a reality”.

A small block of flats designed by Warren on Dorset St in Christchurch in 1956 was an early declaration of intent from an architect who once famously declared that he had never met a straight line he didn't like.

He said the flats were branded by tour bus drivers as “the ugliest buildings in Christchurch”, but the accolade was “the best advert ever for a break-through young architect to get noticed”.

They were the first of many groundbreaking homes designed by Warren, including the famed Ballantynes’ house and his own parents home on Queens Ave, but he was not content to remain in the domestic realm.

Dacombe said Warren “always had a good eye for what he called the ‘main chance’”.

Famed conductor Leonard Bernstein performed at the Town Hall in 1974 and was full of praise.

“I’m crazy about it – very envious, I wish we had something like it in New York,” he told The Press.

“I was very impressed by that combination of vastness and intimacy that the architects have somehow achieved in the hall itself.”

“Working with Miles was an incredibly rich experience full of vicissitudes as Miles’ moods moved from the excitement of challenging commissions to, at times, the lows of missing out on them,’’ Dacombe said in his eulogy.

“His moods could certainly be challenging as he raged around the studio draughting room, berating individuals for not meeting the high standards he had set. No one was spared.

“[But,] no sooner had the outburst occurred, it was over, and Miles would return to his chatty pleasant self.”

And the success was often at the expense of other aspects of his life. His niece, Sarah Smith, said Warren once missed the christening of his goddaughter because he was working in the office on a Sunday.

“We all knew he was very much a part of our small family, but we all knew that his heart and his life and everything was involved in his work and his architecture.

“He didn’t always make family gatherings, but we were all very proud of what he did.”

He found respite restoring his historic homestead, Ohinetai, above Governors Bay at the head of Lyttelton Harbour.

Warren purchased the dilapidated property in 1976 with his sister Pauline and her husband John Trengrove. They set to restoring the home and creating an ornamental garden in the grounds.

“We were amateurs practising an art rather than having to be professional architects. We didn't have a client and we could do what we damn well liked and make our own mistakes.”

The couple moved out in the 1980s and Warren purchased their share. Warren had hoped to remain at the home until his death.

“I will live here as long as I can, but at some stage I might be known as that grumpy old bastard on the first floor.”

Warren delighted in the restoration of the Town Hall and cut the ribbon when it reopened in 2019.

He left Ohinetahi just after his 90th birthday in 2017 and moved into a retirement village as he became too frail to get about the large house.

But Smith said he still had a keen interest in the rebuild of central Christchurch, getting updates from visitors on the restoration of the Christ Church Cathedral and new buildings like Ravenscar House.

“Miles was described by my father as a difficult man. He was very much his own person and absolutely dedicated to the art of architecture and the arts in general.

“He has left an amazing legacy in his buildings, his house and garden, and the numerous substantial gifts he has made to both the arts and architecture and the preservation of heritage buildings.

“He is a true New Zealand icon. We as a family dearly loved him and he will be greatly missed by us all.”

Charlie Gates, THE PRESS, 27 August 2022

RSS Feed

RSS Feed