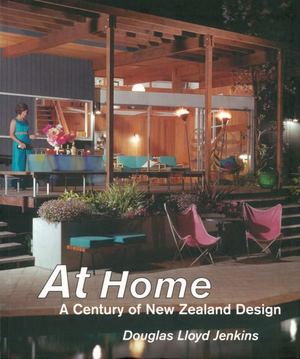

Author Douglas Lloyd Jenkins details the interior design of the Dorset Street Flats.

The most influential house to be built in the South Island during the 1950s wasn’t a house at all but a series of flats. Architect Miles Warren had spent a period in England before returning home to form Warren and Mahoney, but first he went solo on a series of concrete-block flats in Dorset Street, Christchurch. It is often claimed that this was the ‘first conscious use of concrete block and fairface concrete construction inside a New Zealand house or flat’. Concrete block was everywhere in the mid-1950s, but the Dorset Street Flats (1956-57) was one of the new material’s most elegant early outings.

The claim that should be made for the Dorset Street Flats is that it provided one of the first attempts in recent memory at a unit suitable for urban living, built around the needs of a single person not reliant on the state for housing. As Home and Building put it, the flats were to be occupied by ‘young bachelor owners’. Warren had returned from England influenced by English Brutalism, and the result was a series of units that were crisp, sharp-edged and more than a little classical - a new English terrace house for the most English of New Zealand cities. Here were eight one-bedroom apartments, each containing ‘a living room, bedroom, small kitchen and shower, w.c., and basin opening off the bedroom, all within an area of 450 sq ft’. The four ground-floor flats each had their own private courtyard garden, presenting a carefully protected landscape for their occupants to enjoy.

As architecturally exciting as Dorset Street was, any prestige the building is accorded needs to be shared with its original interiors, which are often overlooked in the exultation of its architectural form. These were not box-like rooms, but one intimate space in which elegance derived from rich furnishings that glowed against the matte-white concrete-block walls. In the living room of Warren’s own apartment, modern Scandinavian furniture sat in front of the architect’s built-in wall units (the fold-down fronts of which were faced with neoclassical architectural drawings). A Lucie Rie tea service sat among books on the shelf. These modern elements were complemented with the use of antique furniture and richly coloured Turkish carpets. Whereas antique furniture in previous 1950s interiors had simply seemed old, Warren’s interior suggested a new possibility in which traditional pieces might underpin the modern direction of the interior.

What Warren had created was barely a flat at all, but the prototype for a new urban style of interiorised living that would become better known as the town house. What Dorset Street says most loudly is that not everyone wants a lawn; not everyone wants a family; not everyone wants to put away the things that matter to them; and in this, these small houses were prescient. Today when we look at Dorset Street it is a little hard to imagine that these are not four double-height units, so common did the two-storey town house become. However, when the public first saw the Dorset Street Flats in the pages of Home and Building in 1959, three years after their completion, there was still little like them anywhere in the country.

DOUGLAS LLOYD JENKINS, “At Home: A Century of New Zealand Design”, Godwit (Random House), 2004, ISBN 1-86962-110-7, pp 161-163.

Reproduced with the permission of the author.

The most influential house to be built in the South Island during the 1950s wasn’t a house at all but a series of flats. Architect Miles Warren had spent a period in England before returning home to form Warren and Mahoney, but first he went solo on a series of concrete-block flats in Dorset Street, Christchurch. It is often claimed that this was the ‘first conscious use of concrete block and fairface concrete construction inside a New Zealand house or flat’. Concrete block was everywhere in the mid-1950s, but the Dorset Street Flats (1956-57) was one of the new material’s most elegant early outings.

The claim that should be made for the Dorset Street Flats is that it provided one of the first attempts in recent memory at a unit suitable for urban living, built around the needs of a single person not reliant on the state for housing. As Home and Building put it, the flats were to be occupied by ‘young bachelor owners’. Warren had returned from England influenced by English Brutalism, and the result was a series of units that were crisp, sharp-edged and more than a little classical - a new English terrace house for the most English of New Zealand cities. Here were eight one-bedroom apartments, each containing ‘a living room, bedroom, small kitchen and shower, w.c., and basin opening off the bedroom, all within an area of 450 sq ft’. The four ground-floor flats each had their own private courtyard garden, presenting a carefully protected landscape for their occupants to enjoy.

As architecturally exciting as Dorset Street was, any prestige the building is accorded needs to be shared with its original interiors, which are often overlooked in the exultation of its architectural form. These were not box-like rooms, but one intimate space in which elegance derived from rich furnishings that glowed against the matte-white concrete-block walls. In the living room of Warren’s own apartment, modern Scandinavian furniture sat in front of the architect’s built-in wall units (the fold-down fronts of which were faced with neoclassical architectural drawings). A Lucie Rie tea service sat among books on the shelf. These modern elements were complemented with the use of antique furniture and richly coloured Turkish carpets. Whereas antique furniture in previous 1950s interiors had simply seemed old, Warren’s interior suggested a new possibility in which traditional pieces might underpin the modern direction of the interior.

What Warren had created was barely a flat at all, but the prototype for a new urban style of interiorised living that would become better known as the town house. What Dorset Street says most loudly is that not everyone wants a lawn; not everyone wants a family; not everyone wants to put away the things that matter to them; and in this, these small houses were prescient. Today when we look at Dorset Street it is a little hard to imagine that these are not four double-height units, so common did the two-storey town house become. However, when the public first saw the Dorset Street Flats in the pages of Home and Building in 1959, three years after their completion, there was still little like them anywhere in the country.

DOUGLAS LLOYD JENKINS, “At Home: A Century of New Zealand Design”, Godwit (Random House), 2004, ISBN 1-86962-110-7, pp 161-163.

Reproduced with the permission of the author.