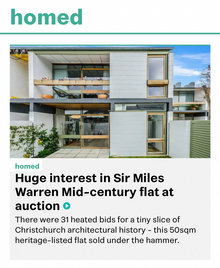

Huge interest in auction of Sir Miles Warren Mid-century flat

A highly sought-after Mid-century flat in a Christchurch block designed by the late Sir Miles Warren has sold under the hammer for $635,000.

The tiny Historic Place Category 1-listed flat in the Dorset Street Flats attracted 31 bids, with two final bidders battling it out to the end.

The flats are a leading example of the “Christchurch School of post-war architecture” and rarely come on the market. The listing noted the flats marked “the emergence of a new kind of residential living in New Zealand, that is, a small-scale group of purpose-designed, modern, modest-sized one-bedroom city flats for minimal living”.

The restoration was designed by Young Architects, and completed after two-and-a-half years of construction. The flats have their own website, and Craig Garlick, the owner of the flat that was occupied by Sir Miles himself says he is thrilled at the positive outcome: “It's been a long slog, frustrating at times, but totally worth it to achieve such a great result. These buildings are such an important part of our national story in terms of design and architecture, and even in the way urban people chose to live.”

Katharine Burrell of First National, who held the listing with James Abell of First National Progressive, said the restoration was designed to preserve all the original character. For example, the kitchen still features open shelving with sliding doors and cut-out finger pulls. The original painted concrete block walls remain, plus a wall of timber shelving with a built-in writing desk. Other interior walls feature board-formed concrete.

“A lot of thought went into the design back in 1956, and it’s so relevant for today,” Burrell said. “I gather Sir Miles was really thrilled when he found the land for this project, because it has a wide street frontage, so all the flats, which are slightly elevated, face the street. The original stables behind have been rebuilt as garaging, and there are communal laundry facilities.”

The agent said it was difficult to price the one-bedroom 50m² flat because the value went “way beyond the bricks and mortar”.

COLLEEN HAWKES, The Press, 29/06/2023.

A highly sought-after Mid-century flat in a Christchurch block designed by the late Sir Miles Warren has sold under the hammer for $635,000.

The tiny Historic Place Category 1-listed flat in the Dorset Street Flats attracted 31 bids, with two final bidders battling it out to the end.

The flats are a leading example of the “Christchurch School of post-war architecture” and rarely come on the market. The listing noted the flats marked “the emergence of a new kind of residential living in New Zealand, that is, a small-scale group of purpose-designed, modern, modest-sized one-bedroom city flats for minimal living”.

The restoration was designed by Young Architects, and completed after two-and-a-half years of construction. The flats have their own website, and Craig Garlick, the owner of the flat that was occupied by Sir Miles himself says he is thrilled at the positive outcome: “It's been a long slog, frustrating at times, but totally worth it to achieve such a great result. These buildings are such an important part of our national story in terms of design and architecture, and even in the way urban people chose to live.”

Katharine Burrell of First National, who held the listing with James Abell of First National Progressive, said the restoration was designed to preserve all the original character. For example, the kitchen still features open shelving with sliding doors and cut-out finger pulls. The original painted concrete block walls remain, plus a wall of timber shelving with a built-in writing desk. Other interior walls feature board-formed concrete.

“A lot of thought went into the design back in 1956, and it’s so relevant for today,” Burrell said. “I gather Sir Miles was really thrilled when he found the land for this project, because it has a wide street frontage, so all the flats, which are slightly elevated, face the street. The original stables behind have been rebuilt as garaging, and there are communal laundry facilities.”

The agent said it was difficult to price the one-bedroom 50m² flat because the value went “way beyond the bricks and mortar”.

COLLEEN HAWKES, The Press, 29/06/2023.

Heritage-listed Sir Miles Warren flats renovated to reveal Mid-century charm

One of the most significant post-earthquake restorations in Christchurch is an architectural Mid-century gem designed by the late architect Sir Miles Warren for himself and three friends – the Dorset Street Flats built in 1956-1957.

The block is not large; it’s probably unrecognised by most Cantabrians, but it’s important enough to have been awarded a Category I Historic Place listing by Heritage New Zealand as a leading example of the “Christchurch School” of post-war architecture.

The listing says the flats marked “the emergence of a new kind of residential living in New Zealand, that is, a small-scale group of purpose-designed, modern, modest-sized one-bedroom city flats for minimal living”.

And it’s not surprising owners of the eight flats are inclined to hang onto them. All the more, now that extensive post-earthquake renovations, designed by Young Architects, have finally been completed.

The flats have their own website that explains the block was “in limbo” following the earthquakes, pending restoration, but that has now been completed after two-and-a-half years of construction. Craig Garlick, the owner of the flat that was occupied by Sir Miles himself says he is thrilled at the positive outcome: “It's been a long slog, frustrating at times, but totally worth it to achieve such a great result. These buildings are such an important part of our national story in terms of design and architecture, and even in the way urban people chose to live.”

Now, one of the flats built for Sir Miles’ architect friend Michael Weston has been publicly listed for the first time – over the past 65 years it has been passed through the extended family.

Katharine Burrell of First National, who holds the listing with James Abell, says the restoration was designed to preserve all the original character. For example, the kitchen still features open shelving with sliding doors and cut-out finger pulls. The original painted concrete block walls remain, plus a wall of timber shelving with a built-in writing desk. Other interior walls feature board-formed concrete.

“A lot of thought went into the design back in 1956, and it’s so relevant for today,” Burrell says. “I gather Sir Miles was really thrilled when he found the land for this project, because it has a wide street frontage, so all the flats, which are slightly elevated, face the street. The original stables behind have been rebuilt as garaging, and there are communal laundry facilities.”

Burrell says the flat will go to auction, as it’s difficult to put a value on it: “Its value is well beyond the bricks and mortar. It has been really tricky to know what it might be worth – it’s not just a sunny one-bedroom unit that’s nice and central in Christchurch; there’s also the value of the heritage aspect.”

The auction of the flat at 14 Dorset Street will take place on Thursday, June 29, 2023.

COLLEEN HAWKES, The Press, 13/06/2023.

One of the most significant post-earthquake restorations in Christchurch is an architectural Mid-century gem designed by the late architect Sir Miles Warren for himself and three friends – the Dorset Street Flats built in 1956-1957.

The block is not large; it’s probably unrecognised by most Cantabrians, but it’s important enough to have been awarded a Category I Historic Place listing by Heritage New Zealand as a leading example of the “Christchurch School” of post-war architecture.

The listing says the flats marked “the emergence of a new kind of residential living in New Zealand, that is, a small-scale group of purpose-designed, modern, modest-sized one-bedroom city flats for minimal living”.

And it’s not surprising owners of the eight flats are inclined to hang onto them. All the more, now that extensive post-earthquake renovations, designed by Young Architects, have finally been completed.

The flats have their own website that explains the block was “in limbo” following the earthquakes, pending restoration, but that has now been completed after two-and-a-half years of construction. Craig Garlick, the owner of the flat that was occupied by Sir Miles himself says he is thrilled at the positive outcome: “It's been a long slog, frustrating at times, but totally worth it to achieve such a great result. These buildings are such an important part of our national story in terms of design and architecture, and even in the way urban people chose to live.”

Now, one of the flats built for Sir Miles’ architect friend Michael Weston has been publicly listed for the first time – over the past 65 years it has been passed through the extended family.

Katharine Burrell of First National, who holds the listing with James Abell, says the restoration was designed to preserve all the original character. For example, the kitchen still features open shelving with sliding doors and cut-out finger pulls. The original painted concrete block walls remain, plus a wall of timber shelving with a built-in writing desk. Other interior walls feature board-formed concrete.

“A lot of thought went into the design back in 1956, and it’s so relevant for today,” Burrell says. “I gather Sir Miles was really thrilled when he found the land for this project, because it has a wide street frontage, so all the flats, which are slightly elevated, face the street. The original stables behind have been rebuilt as garaging, and there are communal laundry facilities.”

Burrell says the flat will go to auction, as it’s difficult to put a value on it: “Its value is well beyond the bricks and mortar. It has been really tricky to know what it might be worth – it’s not just a sunny one-bedroom unit that’s nice and central in Christchurch; there’s also the value of the heritage aspect.”

The auction of the flat at 14 Dorset Street will take place on Thursday, June 29, 2023.

COLLEEN HAWKES, The Press, 13/06/2023.

Heritage building once labelled Christchurch's 'ugliest' secures $240,000 grant

Some city councillors are questioning the principle of giving heritage-listed flats once labelled Christchurch's ugliest a grant of nearly $250,000 when a mobile library is facing closure.

The Dorset St block consists of eight, one-bedroom flats, which were built in 1956-57 and designed by leading architect Sir Miles Warren.

When granted heritage status in 2010, adviser Christine Whybrew said while the building housing the flats was once regarded the city's ugliest, it was ahead of its time.

Council staff said the flats were an internationally-recognised piece of architecture. They were severely damaged in the February 2011 earthquake and remain unoccupied.

Council staff had recommended spending $366,580 on the flats – but the majority of councillors voted against this and instead lowered the grant to $240,000.

The council will pay for the grant out of its Heritage Incentive Grant fund, which has annual budget of about $1.5 million for the 2021 financial year.

During a debate, some councillors questioned the purpose of the fund if a category-1 building could not access it, while others did not back giving the owners a helping hand with ratepayer money.

Sam MacDonald said he did not want an attitude of “because there’s money in a budget, we should therefore spend it”.

“It does become frustrating, because it becomes a constant excuse.”

MacDonald said the city was making “real sacrifices” presently – providing the proposal to close the $91,000-per-year mobile library service as an example.

James Daniels said the library was important to ratepayers.

“That’s crazy that we say no to that, but yes to this [heritage grant]," he said.

Sara Templeton said councillors agreed to propose closing the mobile library at the same time it signed off on heritage funding in the long-term plan.

“If someone with a category-1 building who has applied for this fund doesn't qualify, I think we really need to seriously re-look at the fund,” she said.

Anne Galloway said an economic value could not be put on the flats, as it was important to the city and its identity.

“Christchurch is Sir Miles Warren's place ... this is something to celebrate and treasure," she said.

Craig Garlick, who owned two flats, said the sensible option for owners would have been to demolish and rebuild on the “prime piece of inner city residential land”, but they were determined to preserve the flats.

“We are grateful for the council’s foresight in offering support to our project," he said.

John Roper-Lindsay, who has owned two of the flats for 13 years with his Judith, said he was delighted and grateful the council approved the grant.

STEVEN WALTON, "The Press", 29/04/2021.

Some city councillors are questioning the principle of giving heritage-listed flats once labelled Christchurch's ugliest a grant of nearly $250,000 when a mobile library is facing closure.

The Dorset St block consists of eight, one-bedroom flats, which were built in 1956-57 and designed by leading architect Sir Miles Warren.

When granted heritage status in 2010, adviser Christine Whybrew said while the building housing the flats was once regarded the city's ugliest, it was ahead of its time.

Council staff said the flats were an internationally-recognised piece of architecture. They were severely damaged in the February 2011 earthquake and remain unoccupied.

Council staff had recommended spending $366,580 on the flats – but the majority of councillors voted against this and instead lowered the grant to $240,000.

The council will pay for the grant out of its Heritage Incentive Grant fund, which has annual budget of about $1.5 million for the 2021 financial year.

During a debate, some councillors questioned the purpose of the fund if a category-1 building could not access it, while others did not back giving the owners a helping hand with ratepayer money.

Sam MacDonald said he did not want an attitude of “because there’s money in a budget, we should therefore spend it”.

“It does become frustrating, because it becomes a constant excuse.”

MacDonald said the city was making “real sacrifices” presently – providing the proposal to close the $91,000-per-year mobile library service as an example.

James Daniels said the library was important to ratepayers.

“That’s crazy that we say no to that, but yes to this [heritage grant]," he said.

Sara Templeton said councillors agreed to propose closing the mobile library at the same time it signed off on heritage funding in the long-term plan.

“If someone with a category-1 building who has applied for this fund doesn't qualify, I think we really need to seriously re-look at the fund,” she said.

Anne Galloway said an economic value could not be put on the flats, as it was important to the city and its identity.

“Christchurch is Sir Miles Warren's place ... this is something to celebrate and treasure," she said.

Craig Garlick, who owned two flats, said the sensible option for owners would have been to demolish and rebuild on the “prime piece of inner city residential land”, but they were determined to preserve the flats.

“We are grateful for the council’s foresight in offering support to our project," he said.

John Roper-Lindsay, who has owned two of the flats for 13 years with his Judith, said he was delighted and grateful the council approved the grant.

STEVEN WALTON, "The Press", 29/04/2021.

Earthquake destroys architects’ legacy

Warren and Mahoney brought a brave new look to Christchurch, writes Kim Triegaardt.

The February earthquake cut a swath of destruction across Christchurch, its deadly scythe destroying a lifetime's work by a duo regarded as among New Zealand's greatest architects, Sir Miles Warren and Maurice Mahoney.

In post-World War II Christchurch, if Warren and Mahoney weren't building up a storm, they were influencing other architects until it became widely accepted that - after the 19th-century Gothic revival and William Morris's romantic Arts and Crafts movement of the early 1900s - Warren and Mahoney's form of brutalism was the third architectural movement to sweep the city.

They were the vortex around which the modernist movement in the 50s, 60s and 70s - known as the Christchurch Style - swirled, drawing attention from all quarters.

"Chimneys were tall and assertive. Windows and doors seemed to have been punched through solid masses. The result looked sculptural, abstract and emphatically anchored in the landscape," says Matt Arnold, of online architecture journal Christchurch Modern, quoting design writer Douglas Lloyd Jenkins.

So what does it mean that most of those iconic representations of that period - such as the Convention Centre, the Crowne Plaza, and Dorset Towers are gone, or going?

Sir Miles Warren doesn't want to answer questions like that.

The normally affable octogenarian is a little jaded after a year of journalists demanding the same answers to the same questions.

How does he feel watching the demolition ball swing through buildings that defined Christchurch?

"It's a bit like bleating over the dead," he says coldly on the phone. "I don't want to talk about it any more.”

While many of his buildings were admired in architectural circles, the Brutalism aesthetic he brought back from London - that a building should demonstrate how it was made - raised more than a few eyebrows. There were murmurings that his first project, the Dorset St flats, built in 1955, were the ugliest buildings in the city. "There was an initial shock to the amount of exposed concrete," he says of the style of buildings that soon followed.

Warren once described the Dorset St flats as "the building that launched the ship”.

He had recently returned from Britain where he had worked as an architect for the the London County Council, immersed in a group of architects relishing post-war Britain. It was an exciting time and they embraced a new architectural ethos they called Brutalism. Back home in New Zealand, Warren continued the modern movement but used concrete blocks instead of bricks and allowed the form of the building to emerge from an analysis of what was in it and how the units were arranged. Warren wanted buildings that had a sense of substance and got rid of "ticky-tacky" walls as he described them, replacing them with solid walls.

He teamed up with fellow architect Maurice Mahoney three years later to work on the Dental Training School and the partnership continued over decades. Among the host of buildings that bore the Warren and Mahoney stamp from the that period were the Christchurch Town Hall, the Crowne Plaza, the Central Library, the AMI building on Latimer Square, Dorset Towers, the Transport Ministry building on Montreal St, the Harewood Memorial Gardens and Crematorium and numerous residential buildings.

Mahoney was celebrating his 50th wedding anniversary in the Crowne Plaza the night of the September 4 earthquake. "It behaved like a dream - exactly as it should have," he told reporters. The hotel was designed as two buildings on separate piles linked with seismic plates that allowed the structure to move. The plates "popped" as they were meant to. It was the piles that failed in February, resulting in the hotel being condemned.

The soggy soil that lies under the banks of the Avon River has also put at risk the town hall, a building often claimed among architects to be among New Zealand's finest.

"What makes this building so special," says architectural historian Dr Jessica Halliday, "is there is such a sense of occasion in the town hall. There are so few architectural experiences as magnificent as it. You walk through a low, unassuming entrance and into the foyer, where there is a sense of space spiralling up above you. It's important socially, too, because the people of Christchurch fought really hard to get a town hall and the whole city got in behind it. It's an inheritance for the city.”

An inheritance that Warren seems determined to keep fighting for. In a recent publication, Ten Thoughts x Ten Leaders, he hints indignantly that no-one has invited him to be part of the discussion around the town hall.

"The issues of the moment may be structural, but the architectural mind is invaluable in directing the structural solution," he writes.

There is, after all, a lot of nostalgia tied up in the town hall for him. Warren and Mahoney won the right to design the building in a competition. Their design met the complex brief and the building went on to be completed on time and within budget.

No-one in Christchurch appears to be putting up the same fight to save the town hall as they have the Christ Church Cathedral. Could it be that Brutalism carried with it echoes of socialism that people don't warm to today?

Warren himself described in his essay Style in New Zealand Architecture, that "we believed in architecture for the masses, architecture solving all the problems of society”.

It was a brave world, but it wasn't a pretty one.

Halliday says that's a matter of opinion, and the fashion of the period is coming back.

"It's desired again, people have a taste for it. The fashion of the period has come back in, as younger generations love what their grandparents have produced.”

Warren and Mahoney's reputation earned them commissions around New Zealand and internationally for big civic projects and several commercial developments. While the firm's founders retired in the 90s, the new generations of architects in the company have brought with them strands of modernism that run through their projects.

Through his buildings, Warren once formed a generation of opinion and ideas - and he seems determined to do it again.

He says, "There will be something later" but is not ready to talk about it.

"It's dragging on longer than I had hoped," he growls.

KIM TRIEGAARDT, "The Press", 09/04/2012.

Warren and Mahoney brought a brave new look to Christchurch, writes Kim Triegaardt.

The February earthquake cut a swath of destruction across Christchurch, its deadly scythe destroying a lifetime's work by a duo regarded as among New Zealand's greatest architects, Sir Miles Warren and Maurice Mahoney.

In post-World War II Christchurch, if Warren and Mahoney weren't building up a storm, they were influencing other architects until it became widely accepted that - after the 19th-century Gothic revival and William Morris's romantic Arts and Crafts movement of the early 1900s - Warren and Mahoney's form of brutalism was the third architectural movement to sweep the city.

They were the vortex around which the modernist movement in the 50s, 60s and 70s - known as the Christchurch Style - swirled, drawing attention from all quarters.

"Chimneys were tall and assertive. Windows and doors seemed to have been punched through solid masses. The result looked sculptural, abstract and emphatically anchored in the landscape," says Matt Arnold, of online architecture journal Christchurch Modern, quoting design writer Douglas Lloyd Jenkins.

So what does it mean that most of those iconic representations of that period - such as the Convention Centre, the Crowne Plaza, and Dorset Towers are gone, or going?

Sir Miles Warren doesn't want to answer questions like that.

The normally affable octogenarian is a little jaded after a year of journalists demanding the same answers to the same questions.

How does he feel watching the demolition ball swing through buildings that defined Christchurch?

"It's a bit like bleating over the dead," he says coldly on the phone. "I don't want to talk about it any more.”

While many of his buildings were admired in architectural circles, the Brutalism aesthetic he brought back from London - that a building should demonstrate how it was made - raised more than a few eyebrows. There were murmurings that his first project, the Dorset St flats, built in 1955, were the ugliest buildings in the city. "There was an initial shock to the amount of exposed concrete," he says of the style of buildings that soon followed.

Warren once described the Dorset St flats as "the building that launched the ship”.

He had recently returned from Britain where he had worked as an architect for the the London County Council, immersed in a group of architects relishing post-war Britain. It was an exciting time and they embraced a new architectural ethos they called Brutalism. Back home in New Zealand, Warren continued the modern movement but used concrete blocks instead of bricks and allowed the form of the building to emerge from an analysis of what was in it and how the units were arranged. Warren wanted buildings that had a sense of substance and got rid of "ticky-tacky" walls as he described them, replacing them with solid walls.

He teamed up with fellow architect Maurice Mahoney three years later to work on the Dental Training School and the partnership continued over decades. Among the host of buildings that bore the Warren and Mahoney stamp from the that period were the Christchurch Town Hall, the Crowne Plaza, the Central Library, the AMI building on Latimer Square, Dorset Towers, the Transport Ministry building on Montreal St, the Harewood Memorial Gardens and Crematorium and numerous residential buildings.

Mahoney was celebrating his 50th wedding anniversary in the Crowne Plaza the night of the September 4 earthquake. "It behaved like a dream - exactly as it should have," he told reporters. The hotel was designed as two buildings on separate piles linked with seismic plates that allowed the structure to move. The plates "popped" as they were meant to. It was the piles that failed in February, resulting in the hotel being condemned.

The soggy soil that lies under the banks of the Avon River has also put at risk the town hall, a building often claimed among architects to be among New Zealand's finest.

"What makes this building so special," says architectural historian Dr Jessica Halliday, "is there is such a sense of occasion in the town hall. There are so few architectural experiences as magnificent as it. You walk through a low, unassuming entrance and into the foyer, where there is a sense of space spiralling up above you. It's important socially, too, because the people of Christchurch fought really hard to get a town hall and the whole city got in behind it. It's an inheritance for the city.”

An inheritance that Warren seems determined to keep fighting for. In a recent publication, Ten Thoughts x Ten Leaders, he hints indignantly that no-one has invited him to be part of the discussion around the town hall.

"The issues of the moment may be structural, but the architectural mind is invaluable in directing the structural solution," he writes.

There is, after all, a lot of nostalgia tied up in the town hall for him. Warren and Mahoney won the right to design the building in a competition. Their design met the complex brief and the building went on to be completed on time and within budget.

No-one in Christchurch appears to be putting up the same fight to save the town hall as they have the Christ Church Cathedral. Could it be that Brutalism carried with it echoes of socialism that people don't warm to today?

Warren himself described in his essay Style in New Zealand Architecture, that "we believed in architecture for the masses, architecture solving all the problems of society”.

It was a brave world, but it wasn't a pretty one.

Halliday says that's a matter of opinion, and the fashion of the period is coming back.

"It's desired again, people have a taste for it. The fashion of the period has come back in, as younger generations love what their grandparents have produced.”

Warren and Mahoney's reputation earned them commissions around New Zealand and internationally for big civic projects and several commercial developments. While the firm's founders retired in the 90s, the new generations of architects in the company have brought with them strands of modernism that run through their projects.

Through his buildings, Warren once formed a generation of opinion and ideas - and he seems determined to do it again.

He says, "There will be something later" but is not ready to talk about it.

"It's dragging on longer than I had hoped," he growls.

KIM TRIEGAARDT, "The Press", 09/04/2012.

'Ugliest' building protected

A block of central Christchurch flats, once described as "one of the ugliest buildings in the city", has been given the highest level of heritage protection.

The New Zealand Historic Places Trust said yesterday it had granted category 1 status to the Dorset St flats, built between 1956 and 1957 as the first major project by eminent architect Sir Miles Warren.

Trust heritage adviser Christine Whybrew said the building was seen as one of the most significant pieces of post-war architecture in New Zealand and was a pivotal work in Warren's career.

"It's a bit of a landmark really – everyone knows the building.”

Whybrew said the building, which locals described as "one of the ugliest" in the city when it was built, was ahead of its time.

"It was a bit of an affront to the local community. There were all these large timber houses and then there was this block of concrete flats. It was quite a dramatic difference.”

She said the trust would ask the Christchurch City Council to elevate the building's status in its district plan "to ensure it has the maximum protection possible".

"The Press", 07/05/2010.

A block of central Christchurch flats, once described as "one of the ugliest buildings in the city", has been given the highest level of heritage protection.

The New Zealand Historic Places Trust said yesterday it had granted category 1 status to the Dorset St flats, built between 1956 and 1957 as the first major project by eminent architect Sir Miles Warren.

Trust heritage adviser Christine Whybrew said the building was seen as one of the most significant pieces of post-war architecture in New Zealand and was a pivotal work in Warren's career.

"It's a bit of a landmark really – everyone knows the building.”

Whybrew said the building, which locals described as "one of the ugliest" in the city when it was built, was ahead of its time.

"It was a bit of an affront to the local community. There were all these large timber houses and then there was this block of concrete flats. It was quite a dramatic difference.”

She said the trust would ask the Christchurch City Council to elevate the building's status in its district plan "to ensure it has the maximum protection possible".

"The Press", 07/05/2010.

Former 'ugliest' building in Chch put forward for heritage status

A block of Christchurch flats, once regarded as the "ugliest" building in the city, may get the highest level of heritage protection.

The Dorset St flats, designed and built by Sir Miles Warren in 1956 and 1957, was his first Christchurch project three years into his distinguished architectural career.

The New Zealand Historic Places Trust wants to give category one status to the flats.

Trust southern region general manager Malcolm Duff calls the flats "a bold statement of postwar architecture" that set the blueprint for modern design nationally.

Warren designed the eight one-bedroom flats for himself and three associates as owner-occupied accommodation, and a flat for each owner to let for income.

When built, Duff said they were soon dubbed "Fort Dorset" for their substantial concrete-block look.

"Tour buses would visit to view what were reputed to be the ugliest buildings in the city.”

However, Duff said they were greatly admired in architectural circles and came to distinguish the "Christchurch school" of postwar architecture that helped shape that type of design around the country.

Category one status was proposed because of their aesthetic, architectural, historical and technological significance, he said.

Warren said the move to recognise the building's history was "an excellent idea”.

"It's really the building that launched a number of ships: it really started modern postwar architecture here.”

He said the building's notoriety had been a "great honour" for him. "It speaks to the effrontery of youth, really.”

Trust heritage adviser Christine Whybrew said the flats marked the emergence of a new kind of residential living, and were recognised as one of the most important "modern-movement" buildings in New Zealand.

"Sir Miles took a total-design approach to the flats by designing built-in furniture and fittings and while there have been some internal alterations over the years, the flats retain many of their original features.”

Peter Howard, who owns the flat that Warren used to live in, said he chose it specifically because of the design.

"It really resonated to me from my childhood – I think most of the people living here identify with the architecture in some way.”

Howard said the "ugliest building" remark had to be understood in the context of the time.

"Most of the other places at the time were red brick, red tile houses: people had never seen anything like it before.”

Public submissions on the flats' proposed status close on March 5. They will be reviewed before a final recommendation is put to the trust's board.

GLENN CONWAY, "The Press", 20/02/2010.

A block of Christchurch flats, once regarded as the "ugliest" building in the city, may get the highest level of heritage protection.

The Dorset St flats, designed and built by Sir Miles Warren in 1956 and 1957, was his first Christchurch project three years into his distinguished architectural career.

The New Zealand Historic Places Trust wants to give category one status to the flats.

Trust southern region general manager Malcolm Duff calls the flats "a bold statement of postwar architecture" that set the blueprint for modern design nationally.

Warren designed the eight one-bedroom flats for himself and three associates as owner-occupied accommodation, and a flat for each owner to let for income.

When built, Duff said they were soon dubbed "Fort Dorset" for their substantial concrete-block look.

"Tour buses would visit to view what were reputed to be the ugliest buildings in the city.”

However, Duff said they were greatly admired in architectural circles and came to distinguish the "Christchurch school" of postwar architecture that helped shape that type of design around the country.

Category one status was proposed because of their aesthetic, architectural, historical and technological significance, he said.

Warren said the move to recognise the building's history was "an excellent idea”.

"It's really the building that launched a number of ships: it really started modern postwar architecture here.”

He said the building's notoriety had been a "great honour" for him. "It speaks to the effrontery of youth, really.”

Trust heritage adviser Christine Whybrew said the flats marked the emergence of a new kind of residential living, and were recognised as one of the most important "modern-movement" buildings in New Zealand.

"Sir Miles took a total-design approach to the flats by designing built-in furniture and fittings and while there have been some internal alterations over the years, the flats retain many of their original features.”

Peter Howard, who owns the flat that Warren used to live in, said he chose it specifically because of the design.

"It really resonated to me from my childhood – I think most of the people living here identify with the architecture in some way.”

Howard said the "ugliest building" remark had to be understood in the context of the time.

"Most of the other places at the time were red brick, red tile houses: people had never seen anything like it before.”

Public submissions on the flats' proposed status close on March 5. They will be reviewed before a final recommendation is put to the trust's board.

GLENN CONWAY, "The Press", 20/02/2010.