Architecture and design magazine Here features story on the Dorset Street Flats, accompanied by photographs by renowned Paris-based kiwi architectural photographer, Mary Gaudin.

THE UGLIEST BUILDING IN TOWN

Issue 18

Heritage Renovation Mid-century classic

Story by Harriet Cowie

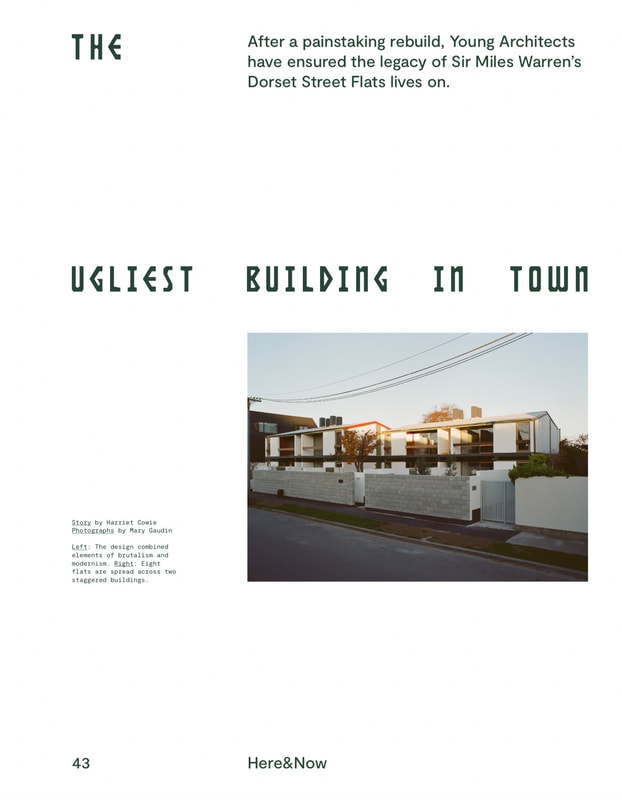

Photographs by Mary Gaudin

The story of the Dorset Street Flats all begins with the hunt for a bachelor pad. It was 1956 when 27-year-old Miles Warren and three of his young, single, male friends set out to build a block of flats in Otautahi Christchurch.

Their plan was simple: they'd create eight one-bedroom apartments and own two each - living in one while they rented the other. They'd already found the perfect section on a quiet street opposite Hagley Park, and though the long, narrow footprint was unusual, Warren considered it the ultimate blank canvas. Given free creative rein by his partners, the burgeoning architect didn't hold back.

Stepping away from the traditional, lightweight timber housing favoured in Christchurch at the time, the Dorset Street Flats' construction was to be a total departure in style and Warren's first significant solo build. He had just returned home following a stint in England, where he'd worked in a graduate role at London County Council during the birth of brutalism. Having spent weekends exploring Europe, encountering the work of contemporary Danish and Swedish architects such as the modernist pioneer Finn Jul, Warren was keen to put his observed architectural influences, experiences and theories into practice. "I came home to New Zealand brimful of ideas and determined to force them on an unsuspecting public," the late architect recalled in his memoir, Miles Warren: An Autobiography.

Made from concrete block construction, the flats span two slightly offset buildings, set back from the road by small courtyards. Though not glaringly obvious, the architect drew inspiration from the traditional English terraced house, reinterpreting its shared party walls and multi-level structure to suit Canterbury's cool climate and the bachelors' lifestyles. As the four owners didn't demand much space, each flat has a footprint of just 45 square metres

- the bedrooms barely squeeze in a double bed - and while they are now painted white, with olive, red and yellow accents, the concrete façade was initially left its natural grey. "Our friends thought we were so poor we could not afford plaster on the concrete block," said Warren.

It was a sharp deviation from the conservative architecture of the time and critics labelled it the "ugliest building in the city". Tour buses are said to have added the notorious "Fort Dorset" to their routes. To his credit, Warren took it as a compliment. "As a young architect, I was proud to achieve such notoriety," he recalled. Worse was yet to come for those naysayers as the flats set off a chain reaction. They proved to be the prototype for a new architectural strand founded on principles of brutalism and modernism with influences from Scandinavian design: the Christchurch Style. Eventually, Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Tonga also recognised the flats' significance, awarding them Category 1 status. Then, in 2011, the Canterbury earthquakes hit, leaving the buildings in bad shape. Constructed from unreinforced concrete block and minimally reinforced in-situ concrete, they had been long overdue for a structural upgrade. There was a mountain of work to be done, but with seven owners and five insurance companies involved, the process was far from straightforward. "It took five years battling with EQC, five years battling with insurance and then two years of construction to get to where we are today," says Greg Young, who headed the restoration project for Young Architects.

The painstaking process of repairing and restrengthening the buildings while maintaining the design integrity was immense. It didn't help that the architects were starting on the back foot. "The more we went through it, the more we found that the construction was quite dramatically on the piss," Young succinctly explains. The original builders had never encountered this type of construction, and you could tell - levels were off, holes were plugged with bricks and hastily plastered over. The off-kilter flats were on such a lean that the separate buildings were touching at the top. Optimistically, Young reframed these failings as an advantage. "I thought, 'We can't get these perfect because they never were perfect,' so that gave us a bit of tolerance.”

The repairs also allowed the architects to incorporate modern comforts into the mid-century homes. Previous owners had told Young of waking up on winter mornings to discover ice on the internal concrete walls, so the works introduced insulation in the roof, floors and some walls, as well as double glazing and underfloor heating. Air-conditioning units were hidden in old hot-water cupboards, and Young added some much-needed storage in the kitchen and bathrooms. Campervan fridge-freezers were retrofitted, too, chosen for their minute proportions. While original joinery was reused where practical, contemporary fixtures and appliances have added an element of modern convenience. "At first glance," Young says, "the flats will appear virtually unchanged from how they were 60 years ago, but they are significantly more comfortable to live in.”

In the past, Young has referred to the project as an "earthquake repair job", but it goes well beyond that. While his team has rescued this important landmark, the modern additions have eliminated many potential drawbacks of living in a mid-century home. Their work on this complex project has spanned more than a decade, and now that it has finally reached completion, we can rest assured that the Ugliest Building in Christchurch will continue to delight and disappoint for years to come.

SIMON FARRELL-GREEN (ed), “Here” magazine, No. 18, Autumn 2023, SFG Media, ISSN 2703-5255, pp. 42-47.

THE UGLIEST BUILDING IN TOWN

Issue 18

Heritage Renovation Mid-century classic

Story by Harriet Cowie

Photographs by Mary Gaudin

The story of the Dorset Street Flats all begins with the hunt for a bachelor pad. It was 1956 when 27-year-old Miles Warren and three of his young, single, male friends set out to build a block of flats in Otautahi Christchurch.

Their plan was simple: they'd create eight one-bedroom apartments and own two each - living in one while they rented the other. They'd already found the perfect section on a quiet street opposite Hagley Park, and though the long, narrow footprint was unusual, Warren considered it the ultimate blank canvas. Given free creative rein by his partners, the burgeoning architect didn't hold back.

Stepping away from the traditional, lightweight timber housing favoured in Christchurch at the time, the Dorset Street Flats' construction was to be a total departure in style and Warren's first significant solo build. He had just returned home following a stint in England, where he'd worked in a graduate role at London County Council during the birth of brutalism. Having spent weekends exploring Europe, encountering the work of contemporary Danish and Swedish architects such as the modernist pioneer Finn Jul, Warren was keen to put his observed architectural influences, experiences and theories into practice. "I came home to New Zealand brimful of ideas and determined to force them on an unsuspecting public," the late architect recalled in his memoir, Miles Warren: An Autobiography.

Made from concrete block construction, the flats span two slightly offset buildings, set back from the road by small courtyards. Though not glaringly obvious, the architect drew inspiration from the traditional English terraced house, reinterpreting its shared party walls and multi-level structure to suit Canterbury's cool climate and the bachelors' lifestyles. As the four owners didn't demand much space, each flat has a footprint of just 45 square metres

- the bedrooms barely squeeze in a double bed - and while they are now painted white, with olive, red and yellow accents, the concrete façade was initially left its natural grey. "Our friends thought we were so poor we could not afford plaster on the concrete block," said Warren.

It was a sharp deviation from the conservative architecture of the time and critics labelled it the "ugliest building in the city". Tour buses are said to have added the notorious "Fort Dorset" to their routes. To his credit, Warren took it as a compliment. "As a young architect, I was proud to achieve such notoriety," he recalled. Worse was yet to come for those naysayers as the flats set off a chain reaction. They proved to be the prototype for a new architectural strand founded on principles of brutalism and modernism with influences from Scandinavian design: the Christchurch Style. Eventually, Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Tonga also recognised the flats' significance, awarding them Category 1 status. Then, in 2011, the Canterbury earthquakes hit, leaving the buildings in bad shape. Constructed from unreinforced concrete block and minimally reinforced in-situ concrete, they had been long overdue for a structural upgrade. There was a mountain of work to be done, but with seven owners and five insurance companies involved, the process was far from straightforward. "It took five years battling with EQC, five years battling with insurance and then two years of construction to get to where we are today," says Greg Young, who headed the restoration project for Young Architects.

The painstaking process of repairing and restrengthening the buildings while maintaining the design integrity was immense. It didn't help that the architects were starting on the back foot. "The more we went through it, the more we found that the construction was quite dramatically on the piss," Young succinctly explains. The original builders had never encountered this type of construction, and you could tell - levels were off, holes were plugged with bricks and hastily plastered over. The off-kilter flats were on such a lean that the separate buildings were touching at the top. Optimistically, Young reframed these failings as an advantage. "I thought, 'We can't get these perfect because they never were perfect,' so that gave us a bit of tolerance.”

The repairs also allowed the architects to incorporate modern comforts into the mid-century homes. Previous owners had told Young of waking up on winter mornings to discover ice on the internal concrete walls, so the works introduced insulation in the roof, floors and some walls, as well as double glazing and underfloor heating. Air-conditioning units were hidden in old hot-water cupboards, and Young added some much-needed storage in the kitchen and bathrooms. Campervan fridge-freezers were retrofitted, too, chosen for their minute proportions. While original joinery was reused where practical, contemporary fixtures and appliances have added an element of modern convenience. "At first glance," Young says, "the flats will appear virtually unchanged from how they were 60 years ago, but they are significantly more comfortable to live in.”

In the past, Young has referred to the project as an "earthquake repair job", but it goes well beyond that. While his team has rescued this important landmark, the modern additions have eliminated many potential drawbacks of living in a mid-century home. Their work on this complex project has spanned more than a decade, and now that it has finally reached completion, we can rest assured that the Ugliest Building in Christchurch will continue to delight and disappoint for years to come.

SIMON FARRELL-GREEN (ed), “Here” magazine, No. 18, Autumn 2023, SFG Media, ISSN 2703-5255, pp. 42-47.