Local South Island lifestyle magazine O3 looks at the restoration of the Dorset Street Flats, as a lead-up to the 2023 Open Christchurch festival.

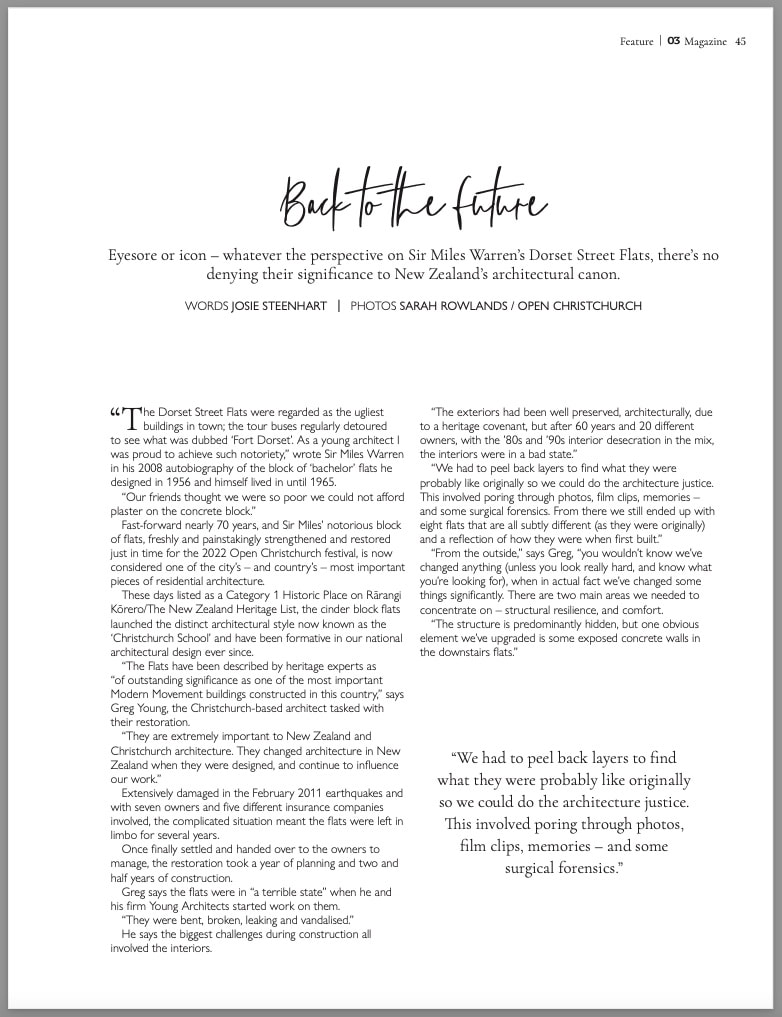

Back to the future

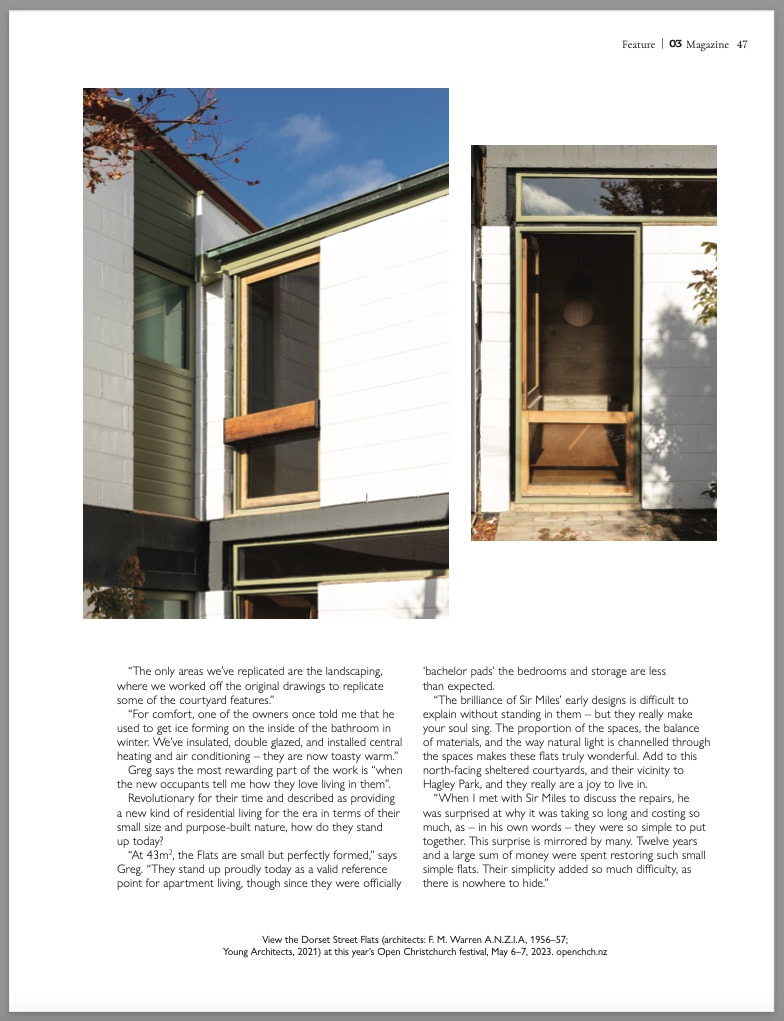

Eyesore or icon – whatever the perspective on Sir Miles Warren’s Dorset Street Flats, there’s no denying their significance to New Zealand’s architectural canon.

WORDS JOSIE STEENHART | PHOTOS SARAH ROWLANDS / OPEN CHRISTCHURCH

“The Dorset Street Flats were regarded as the ugliest buildings in town; the tour buses regularly detoured to see what was dubbed ‘Fort Dorset’. As a young architect I was proud to achieve such notoriety,” wrote Sir Miles Warren in his 2008 autobiography of the block of ‘bachelor’ flats he designed in 1956 and himself lived in until 1965.

“Our friends thought we were so poor we could not afford plaster on the concrete block.”

Fast-forward nearly 70 years, and Sir Miles’ notorious block of flats, freshly and painstakingly strengthened and restored just in time for the 2022 Open Christchurch festival, is now considered one of the city’s – and country’s – most important pieces of residential architecture.

These days listed as a Category 1 Historic Place on Rārangi Kōrero/The New Zealand Heritage List, the cinder block flats launched the distinct architectural style now known as the ‘Christchurch School’ and have been formative in our national architectural design ever since.

“The Flats have been described by heritage experts as “of outstanding significance as one of the most important Modern Movement buildings constructed in this country,” says Greg Young, the Christchurch-based architect tasked with their restoration.

“They are extremely important to New Zealand and Christchurch architecture. They changed architecture in New Zealand when they were designed, and continue to influence our work.”

Extensively damaged in the February 2011 earthquakes and with seven owners and five different insurance companies involved, the complicated situation meant the flats were left in limbo for several years.

Once finally settled and handed over to the owners to manage, the restoration took a year of planning and two and half years of construction.

Greg says the flats were in “a terrible state” when he and his firm Young Architects started work on them.

“They were bent, broken, leaking and vandalised.”

He says the biggest challenges during construction all involved the interiors.

“The exteriors had been well preserved, architecturally, due to a heritage covenant, but after 60 years and 20 different owners, with the ’80s and ’90s interior desecration in the mix, the interiors were in a bad state.”

“We had to peel back layers to find what they were probably like originally so we could do the architecture justice. This involved poring through photos, film clips, memories – and some surgical forensics. From there we still ended up with eight flats that are all subtly different (as they were originally) and a reflection of how they were when first built.”

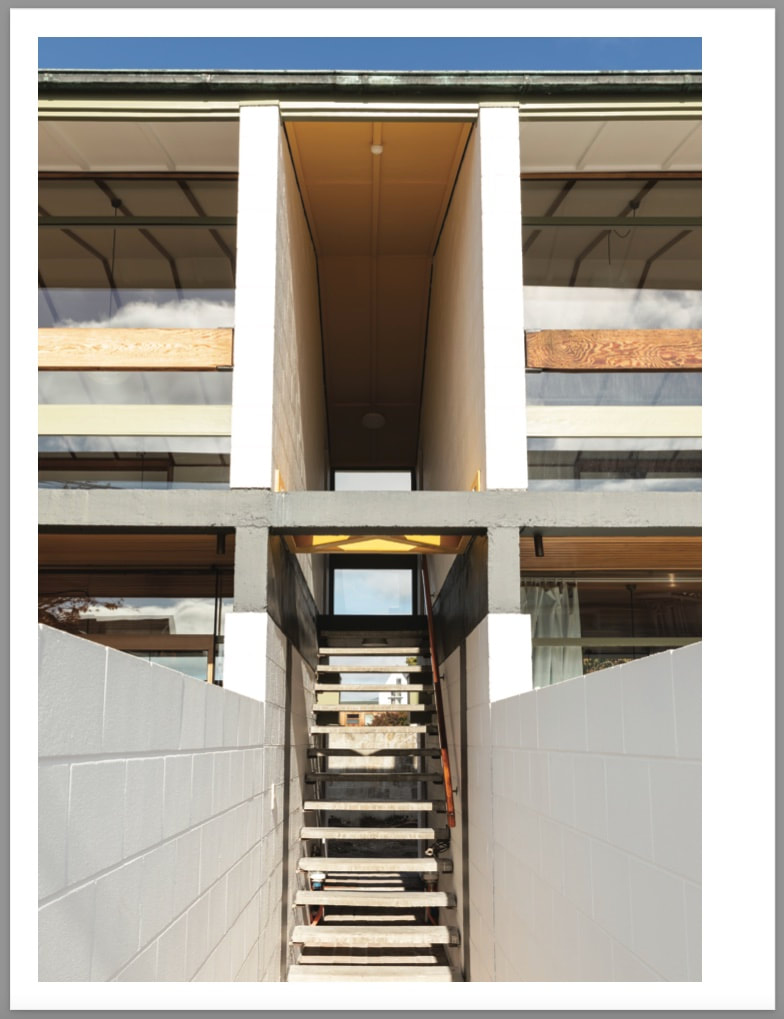

“From the outside,” says Greg, “you wouldn’t know we’ve changed anything (unless you look really hard, and know what you’re looking for), when in actual fact we’ve changed some things significantly. There are two main areas we needed to concentrate on – structural resilience, and comfort.

“The structure is predominantly hidden, but one obvious element we’ve upgraded is some exposed concrete walls in the downstairs flats.”

“The only areas we’ve replicated are the landscaping, where we worked off the original drawings to replicate some of the courtyard features.”

“For comfort, one of the owners once told me that he used to get ice forming on the inside of the bathroom in winter. We’ve insulated, double glazed, and installed central heating and air conditioning – they are now toasty warm.”

Greg says the most rewarding part of the work is “when the new occupants tell me how they love living in them”.

Revolutionary for their time and described as providing a new kind of residential living for the era in terms of their small size and purpose-built nature, how do they stand up today?

“At 43m2, the Flats are small but perfectly formed,” says Greg. “They stand up proudly today as a valid reference point for apartment living, though since they were officially ‘bachelor pads’ the bedrooms and storage are less than expected.

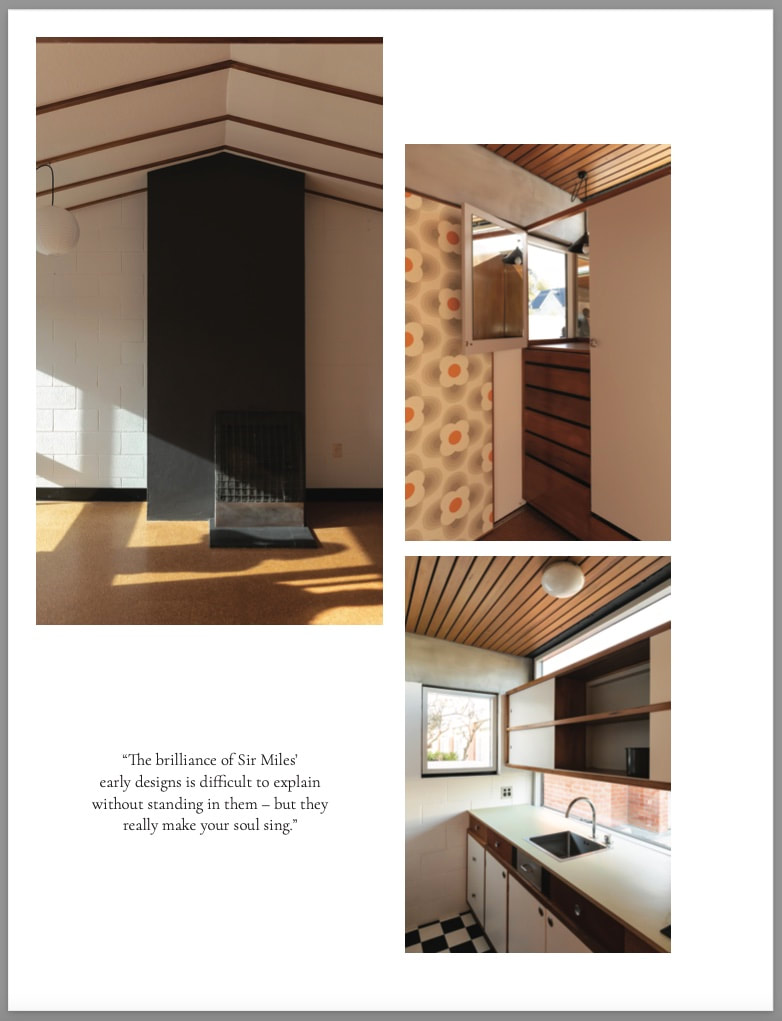

“The brilliance of Sir Miles’ early designs is difficult to explain without standing in them – but they really make your soul sing. The proportion of the spaces, the balance of materials, and the way natural light is channelled through the spaces makes these flats truly wonderful. Add to this north-facing sheltered courtyards, and their vicinity to Hagley Park, and they really are a joy to live in.

“When I met with Sir Miles to discuss the repairs, he was surprised at why it was taking so long and costing so much, as – in his own words – they were so simple to put together. This surprise is mirrored by many. Twelve years and a large sum of money were spent restoring such small simple flats. Their simplicity added so much difficulty, as there is nowhere to hide.”

View the Dorset Street Flats (architects: F. M. Warren A.N.Z.I.A, 1956–57; Young Architects, 2021) at this year’s Open Christchurch festival, May 6–7, 2023. openchch.nz

JOSIE STEENHART (ed), “03 Magazine”, April 2023, Allied Press Magazines, ISSN 2816-0711, pp. 44-47.

Back to the future

Eyesore or icon – whatever the perspective on Sir Miles Warren’s Dorset Street Flats, there’s no denying their significance to New Zealand’s architectural canon.

WORDS JOSIE STEENHART | PHOTOS SARAH ROWLANDS / OPEN CHRISTCHURCH

“The Dorset Street Flats were regarded as the ugliest buildings in town; the tour buses regularly detoured to see what was dubbed ‘Fort Dorset’. As a young architect I was proud to achieve such notoriety,” wrote Sir Miles Warren in his 2008 autobiography of the block of ‘bachelor’ flats he designed in 1956 and himself lived in until 1965.

“Our friends thought we were so poor we could not afford plaster on the concrete block.”

Fast-forward nearly 70 years, and Sir Miles’ notorious block of flats, freshly and painstakingly strengthened and restored just in time for the 2022 Open Christchurch festival, is now considered one of the city’s – and country’s – most important pieces of residential architecture.

These days listed as a Category 1 Historic Place on Rārangi Kōrero/The New Zealand Heritage List, the cinder block flats launched the distinct architectural style now known as the ‘Christchurch School’ and have been formative in our national architectural design ever since.

“The Flats have been described by heritage experts as “of outstanding significance as one of the most important Modern Movement buildings constructed in this country,” says Greg Young, the Christchurch-based architect tasked with their restoration.

“They are extremely important to New Zealand and Christchurch architecture. They changed architecture in New Zealand when they were designed, and continue to influence our work.”

Extensively damaged in the February 2011 earthquakes and with seven owners and five different insurance companies involved, the complicated situation meant the flats were left in limbo for several years.

Once finally settled and handed over to the owners to manage, the restoration took a year of planning and two and half years of construction.

Greg says the flats were in “a terrible state” when he and his firm Young Architects started work on them.

“They were bent, broken, leaking and vandalised.”

He says the biggest challenges during construction all involved the interiors.

“The exteriors had been well preserved, architecturally, due to a heritage covenant, but after 60 years and 20 different owners, with the ’80s and ’90s interior desecration in the mix, the interiors were in a bad state.”

“We had to peel back layers to find what they were probably like originally so we could do the architecture justice. This involved poring through photos, film clips, memories – and some surgical forensics. From there we still ended up with eight flats that are all subtly different (as they were originally) and a reflection of how they were when first built.”

“From the outside,” says Greg, “you wouldn’t know we’ve changed anything (unless you look really hard, and know what you’re looking for), when in actual fact we’ve changed some things significantly. There are two main areas we needed to concentrate on – structural resilience, and comfort.

“The structure is predominantly hidden, but one obvious element we’ve upgraded is some exposed concrete walls in the downstairs flats.”

“The only areas we’ve replicated are the landscaping, where we worked off the original drawings to replicate some of the courtyard features.”

“For comfort, one of the owners once told me that he used to get ice forming on the inside of the bathroom in winter. We’ve insulated, double glazed, and installed central heating and air conditioning – they are now toasty warm.”

Greg says the most rewarding part of the work is “when the new occupants tell me how they love living in them”.

Revolutionary for their time and described as providing a new kind of residential living for the era in terms of their small size and purpose-built nature, how do they stand up today?

“At 43m2, the Flats are small but perfectly formed,” says Greg. “They stand up proudly today as a valid reference point for apartment living, though since they were officially ‘bachelor pads’ the bedrooms and storage are less than expected.

“The brilliance of Sir Miles’ early designs is difficult to explain without standing in them – but they really make your soul sing. The proportion of the spaces, the balance of materials, and the way natural light is channelled through the spaces makes these flats truly wonderful. Add to this north-facing sheltered courtyards, and their vicinity to Hagley Park, and they really are a joy to live in.

“When I met with Sir Miles to discuss the repairs, he was surprised at why it was taking so long and costing so much, as – in his own words – they were so simple to put together. This surprise is mirrored by many. Twelve years and a large sum of money were spent restoring such small simple flats. Their simplicity added so much difficulty, as there is nowhere to hide.”

View the Dorset Street Flats (architects: F. M. Warren A.N.Z.I.A, 1956–57; Young Architects, 2021) at this year’s Open Christchurch festival, May 6–7, 2023. openchch.nz

JOSIE STEENHART (ed), “03 Magazine”, April 2023, Allied Press Magazines, ISSN 2816-0711, pp. 44-47.