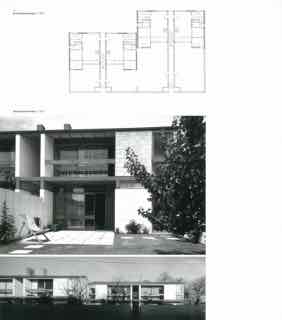

Miles Warren and Dorset Street Flats.

Warren and Mahoney are best known, at least in architectural circles, for their early work, starting with the Dorset Street Flats in 1956 and culminating in the design of the Christchurch Town Hall in 1966, a brief ten years. Others included the Christchurch Dental School, the Harewood Crematorium, the Chapman block at Christ’s College, office and flat at 65 Cambridge Terrace, the Wool Exchange, Christchurch College (now College House) and the Canterbury Students’ Union.

All these buildings were designed within what is now regarded as the high point of New Zealand modernism, whose basic tenets were that the form should derive from, or at least be generated by, what took place in the building, its function, and, that how the building was built, and with what materials, be demonstrated.

The briefs were mostly for special one-off functions, a crematorium, a wool exchange, a student union and a university hall. All were built with concrete, fairface exposed inside and out, in situ, leading to precast concrete in more and more complex forms, the ultimate tour de force, ‘look how clever we are’ being the Canterbury Students’ Union, aptly described by Professor Danks as a ‘skeletal encrustacean’.

European travels and working at the London City Council had introduced me to the substance and weight of masonry walls, the complete opposite of our New Zealand light-weight, thin timber wall tradition. The flats in Dorset Street started our use of load bearing reinforced concrete block, developed with the brilliant engineer Lyall Holmes. The technique and resultant forms were developed via a number of small blocks of flats and reached its peak at 65 Cambridge Terrace and Christchurch College.

The exposed concrete and white painted concrete block contrasted with timber roofs of exposed rafters and boarding, carried on the New Zealand tradition of architects trained and thinking like carpenters, a tradition which culminated in the next generation of architects.

Miles Warren

In his forward to this book Sir Miles refers to his European travels and his working stint at the London City Council. He was there at the time of the New Brutalism style in architecture and gained an appreciation of the detailing of weighty masonry and precast concrete. This experience, coupled with his earlier New Zealand ‘carpentry’ craft of assembling and connecting elements of buildings, and his already well trained eye for proportion, scale and form, gave rise to a new way of detailing buildings that expressed this ‘connection’ process. It was called ‘negative detailing’ and started a new wave in architecture in New Zealand that was the beginning of what became the ‘Christchurch Style’ of the 1960s.

By way of example, the Dorset Street Flats were designed and constructed demonstrating this technique of making. Considerable attention was given to building junctions; concrete block masonry overhung concrete foundations and lintel beams to express and separate the two materials; door and window frames incorporated recessed packers, scribed to the concrete block opening which expressed the timber frame of the door or window surround; gable end barges were designed to hover above the raking gable walls with appropriate recessed flashings (no overhangs, note) and the inevitable barge roll to the corrugated iron roofs neatly concluded at the spoutings.

This technique of detailing and joining materials continued to be developed by the craftsman and his followers, and became the refined and sophisticated aesthetic of Christchurch architecture.

At all times the principles of practical detailing, designed to keep out the weather and ensure durability were paramount and the architecture became clear and crisp, well ordered and neatly proportioned as a consequence. Hours were spent on the placement of a window in a gable wall to achieve balance and proportion. Glazed or boarded doors were designed with finely proportioned and elegant stiles and carefully, visually weighted top bottom and middle rails, mortised and tenoned and wedged and glued together. Even neatly proportioned book shelves in stained and varnished meranti timber and polished brass plates and screws were given full design and detailed attention, to such an extent that in the ‘60s the firm was affectionately known as Warren and Meranti. What made this making process perhaps logical and precise was that the palette of materials used were restricted - off-form concrete with expressed boarded patterning, concrete block (usually painted white), corrugated iron roofing (membrane roofing was not available then and flat roofs were done with Neuchatel asphalt) stained and varnished meranti timber with contrasting satin clear varnished rimu boarding, cedar sales and clear glass, was about it.

Barry Dacombe

“New Territory: Warren And Mahoney: 50 Years Of New Zealand Architecture”, Warren and Mahoney (eds), Balasoglou Books, 2005, ISBN 0-9582625-2-7, p 16, p 27, pp 120-121, p 126.

Warren and Mahoney are best known, at least in architectural circles, for their early work, starting with the Dorset Street Flats in 1956 and culminating in the design of the Christchurch Town Hall in 1966, a brief ten years. Others included the Christchurch Dental School, the Harewood Crematorium, the Chapman block at Christ’s College, office and flat at 65 Cambridge Terrace, the Wool Exchange, Christchurch College (now College House) and the Canterbury Students’ Union.

All these buildings were designed within what is now regarded as the high point of New Zealand modernism, whose basic tenets were that the form should derive from, or at least be generated by, what took place in the building, its function, and, that how the building was built, and with what materials, be demonstrated.

The briefs were mostly for special one-off functions, a crematorium, a wool exchange, a student union and a university hall. All were built with concrete, fairface exposed inside and out, in situ, leading to precast concrete in more and more complex forms, the ultimate tour de force, ‘look how clever we are’ being the Canterbury Students’ Union, aptly described by Professor Danks as a ‘skeletal encrustacean’.

European travels and working at the London City Council had introduced me to the substance and weight of masonry walls, the complete opposite of our New Zealand light-weight, thin timber wall tradition. The flats in Dorset Street started our use of load bearing reinforced concrete block, developed with the brilliant engineer Lyall Holmes. The technique and resultant forms were developed via a number of small blocks of flats and reached its peak at 65 Cambridge Terrace and Christchurch College.

The exposed concrete and white painted concrete block contrasted with timber roofs of exposed rafters and boarding, carried on the New Zealand tradition of architects trained and thinking like carpenters, a tradition which culminated in the next generation of architects.

Miles Warren

In his forward to this book Sir Miles refers to his European travels and his working stint at the London City Council. He was there at the time of the New Brutalism style in architecture and gained an appreciation of the detailing of weighty masonry and precast concrete. This experience, coupled with his earlier New Zealand ‘carpentry’ craft of assembling and connecting elements of buildings, and his already well trained eye for proportion, scale and form, gave rise to a new way of detailing buildings that expressed this ‘connection’ process. It was called ‘negative detailing’ and started a new wave in architecture in New Zealand that was the beginning of what became the ‘Christchurch Style’ of the 1960s.

By way of example, the Dorset Street Flats were designed and constructed demonstrating this technique of making. Considerable attention was given to building junctions; concrete block masonry overhung concrete foundations and lintel beams to express and separate the two materials; door and window frames incorporated recessed packers, scribed to the concrete block opening which expressed the timber frame of the door or window surround; gable end barges were designed to hover above the raking gable walls with appropriate recessed flashings (no overhangs, note) and the inevitable barge roll to the corrugated iron roofs neatly concluded at the spoutings.

This technique of detailing and joining materials continued to be developed by the craftsman and his followers, and became the refined and sophisticated aesthetic of Christchurch architecture.

At all times the principles of practical detailing, designed to keep out the weather and ensure durability were paramount and the architecture became clear and crisp, well ordered and neatly proportioned as a consequence. Hours were spent on the placement of a window in a gable wall to achieve balance and proportion. Glazed or boarded doors were designed with finely proportioned and elegant stiles and carefully, visually weighted top bottom and middle rails, mortised and tenoned and wedged and glued together. Even neatly proportioned book shelves in stained and varnished meranti timber and polished brass plates and screws were given full design and detailed attention, to such an extent that in the ‘60s the firm was affectionately known as Warren and Meranti. What made this making process perhaps logical and precise was that the palette of materials used were restricted - off-form concrete with expressed boarded patterning, concrete block (usually painted white), corrugated iron roofing (membrane roofing was not available then and flat roofs were done with Neuchatel asphalt) stained and varnished meranti timber with contrasting satin clear varnished rimu boarding, cedar sales and clear glass, was about it.

Barry Dacombe

“New Territory: Warren And Mahoney: 50 Years Of New Zealand Architecture”, Warren and Mahoney (eds), Balasoglou Books, 2005, ISBN 0-9582625-2-7, p 16, p 27, pp 120-121, p 126.