Europe, London and Alton West

“I was in London at the LCC, extraordinarily fortunate to be sitting right in the middle of the birth of Brutalism… and like so many architects, came home brimful of ideas and determined to force them onto an unsuspecting public.”[1]

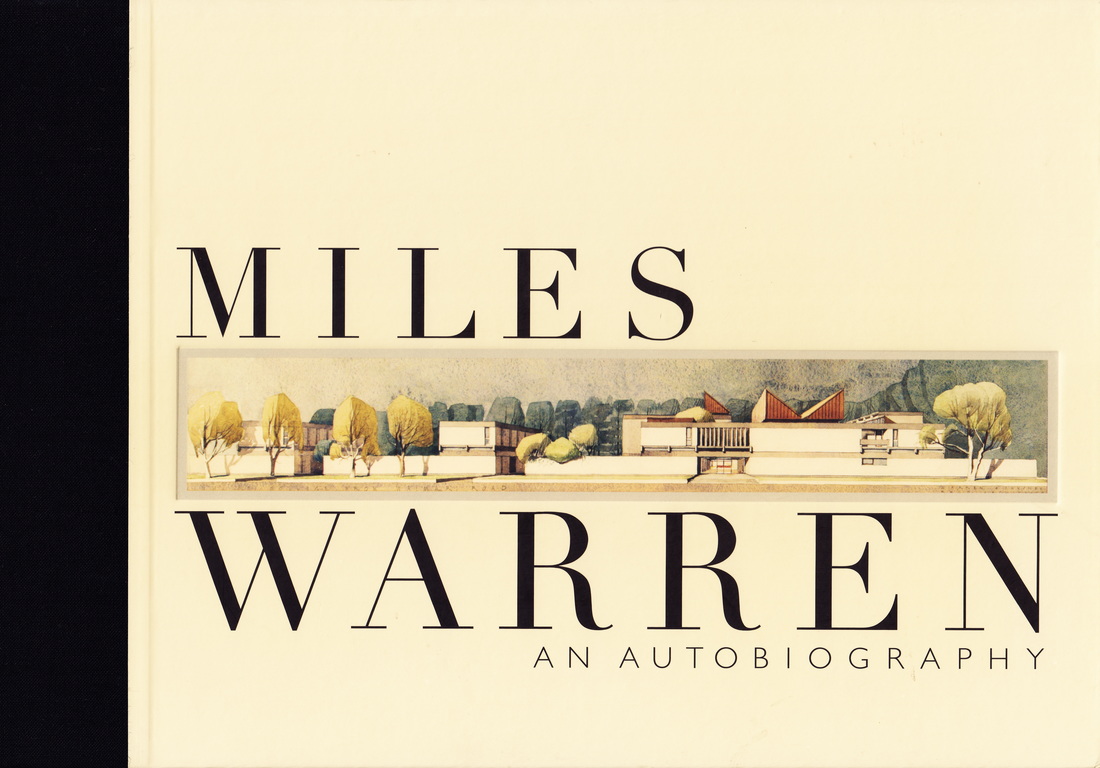

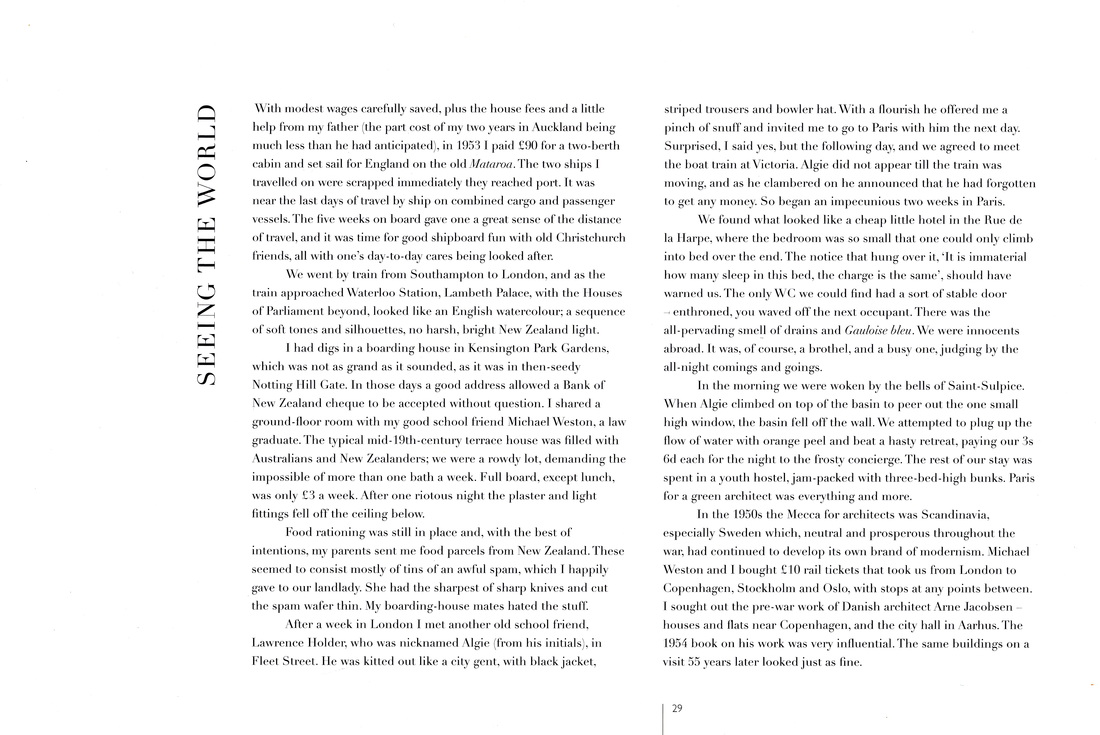

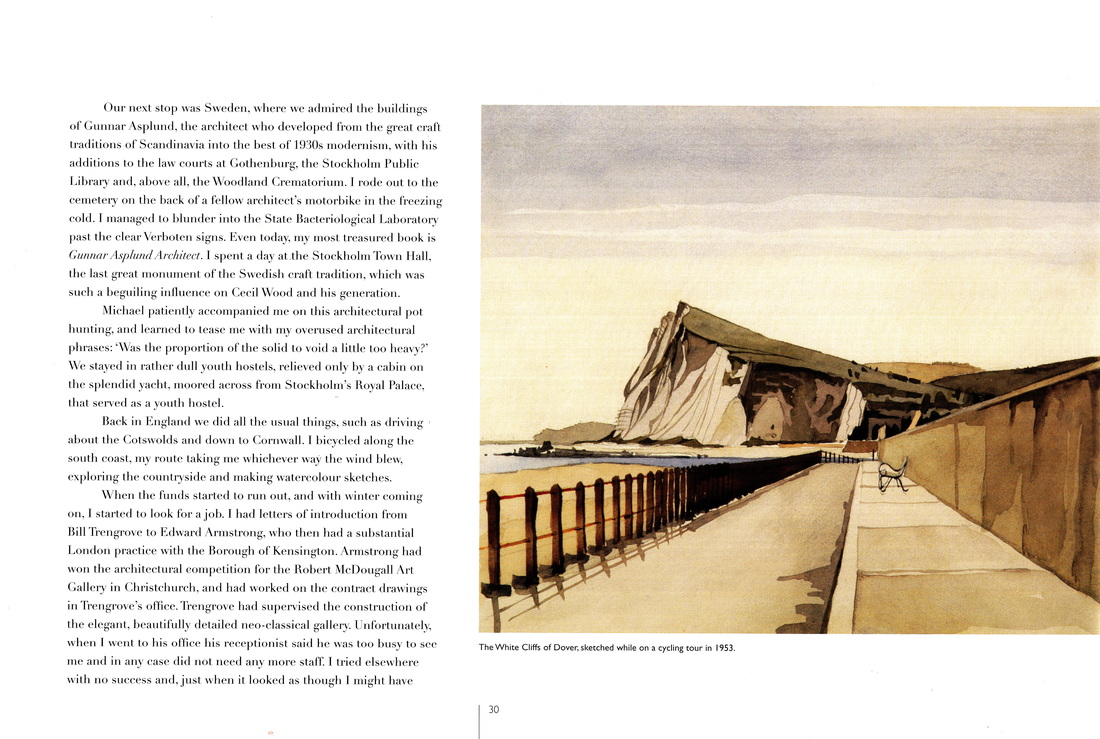

After graduating from the Auckland University College School of Architecture in 1950, and having spent a further two years working in the Christchurch offices of architect Bill Trengrove, Miles Warren packed his bags, and in 1953 set sail for England. Arriving in London via Southampton, he found a flat in a Notting Hill Gate terrace house full of fellow antipodeans, sharing his ground floor-room with old school friend (and future partner in Dorset Street Flats), recently graduated lawyer Michael Weston.[2] A short time later, the two set off on the obligatory tour of ’50s architectural hotspot, Scandinavia, with Weston indulging his friend’s fascination for the new modernism:

“Michael patiently accompanied me on this architectural pot hunting, and learned to tease me with my overused architectural phrases: “Was the proportion of the solid to void a little too heavy?””[3]

Visiting Copenhagen, Stockholm and Oslo among others, viewing the works of Danish architect Arne Jacobsen and touring the house of Danish furniture designer Finn Juhl, Warren took in the Scandinavian style which had flourished in the wake of the end of the war. But money soon ran low, and attention turned to finding employment.

“When the funds started to run out, and with winter coming on, I started to look for a job. … and, just when it looked as though I might have to find work outside architecture, the London City Council advertised for recently qualified architects.

About 20 of us turned up at the appointed time, each clutching rolls of drawings. We were ushered into a grand space, with three dignified assessors sitting high up like a court in a neo-classical apse. They looked at the drawings of my only house commission. “There is a lot of wood in this house, young man.” “Yes sir, New Zealand is a timber-producing country,” I replied. “What about putting him with the Roehampton group? He might add some useful experience,” said one assessor to the other. So I was hired, and with the greatest good luck joined a group that was to produce some of the best London City Council architecture in its heyday.”[4]

After graduating from the Auckland University College School of Architecture in 1950, and having spent a further two years working in the Christchurch offices of architect Bill Trengrove, Miles Warren packed his bags, and in 1953 set sail for England. Arriving in London via Southampton, he found a flat in a Notting Hill Gate terrace house full of fellow antipodeans, sharing his ground floor-room with old school friend (and future partner in Dorset Street Flats), recently graduated lawyer Michael Weston.[2] A short time later, the two set off on the obligatory tour of ’50s architectural hotspot, Scandinavia, with Weston indulging his friend’s fascination for the new modernism:

“Michael patiently accompanied me on this architectural pot hunting, and learned to tease me with my overused architectural phrases: “Was the proportion of the solid to void a little too heavy?””[3]

Visiting Copenhagen, Stockholm and Oslo among others, viewing the works of Danish architect Arne Jacobsen and touring the house of Danish furniture designer Finn Juhl, Warren took in the Scandinavian style which had flourished in the wake of the end of the war. But money soon ran low, and attention turned to finding employment.

“When the funds started to run out, and with winter coming on, I started to look for a job. … and, just when it looked as though I might have to find work outside architecture, the London City Council advertised for recently qualified architects.

About 20 of us turned up at the appointed time, each clutching rolls of drawings. We were ushered into a grand space, with three dignified assessors sitting high up like a court in a neo-classical apse. They looked at the drawings of my only house commission. “There is a lot of wood in this house, young man.” “Yes sir, New Zealand is a timber-producing country,” I replied. “What about putting him with the Roehampton group? He might add some useful experience,” said one assessor to the other. So I was hired, and with the greatest good luck joined a group that was to produce some of the best London City Council architecture in its heyday.”[4]

The London County Council and the Alton East and West Estates

The years immediately following the war had seen Labour’s national housing policy aimed squarely at resettling the huge numbers left homeless by the blitz. However after 1950, the London County Council (LCC) was relieved of some of that responsibility when more control was passed to the boroughs. Freed from the urgency of meeting immediate needs, the LCC could take a longer term view, spend more time on design, and pursue it’s ideals of a socialist housing utopia. And modernism was rapidly becoming the official style of the new welfare state.

By the mid-1950s, the LCC had the largest Architect's Department in the country, attracting the brightest talent in British architecture, with over five thousand staff, including around ten housing sections, each with about twenty architects.[5] One such section was the Roehampton Group, with it's two teams - East and West.

The years immediately following the war had seen Labour’s national housing policy aimed squarely at resettling the huge numbers left homeless by the blitz. However after 1950, the London County Council (LCC) was relieved of some of that responsibility when more control was passed to the boroughs. Freed from the urgency of meeting immediate needs, the LCC could take a longer term view, spend more time on design, and pursue it’s ideals of a socialist housing utopia. And modernism was rapidly becoming the official style of the new welfare state.

By the mid-1950s, the LCC had the largest Architect's Department in the country, attracting the brightest talent in British architecture, with over five thousand staff, including around ten housing sections, each with about twenty architects.[5] One such section was the Roehampton Group, with it's two teams - East and West.

Mount Clare, built in 1772 for George Clive.

Mount Clare, built in 1772 for George Clive.

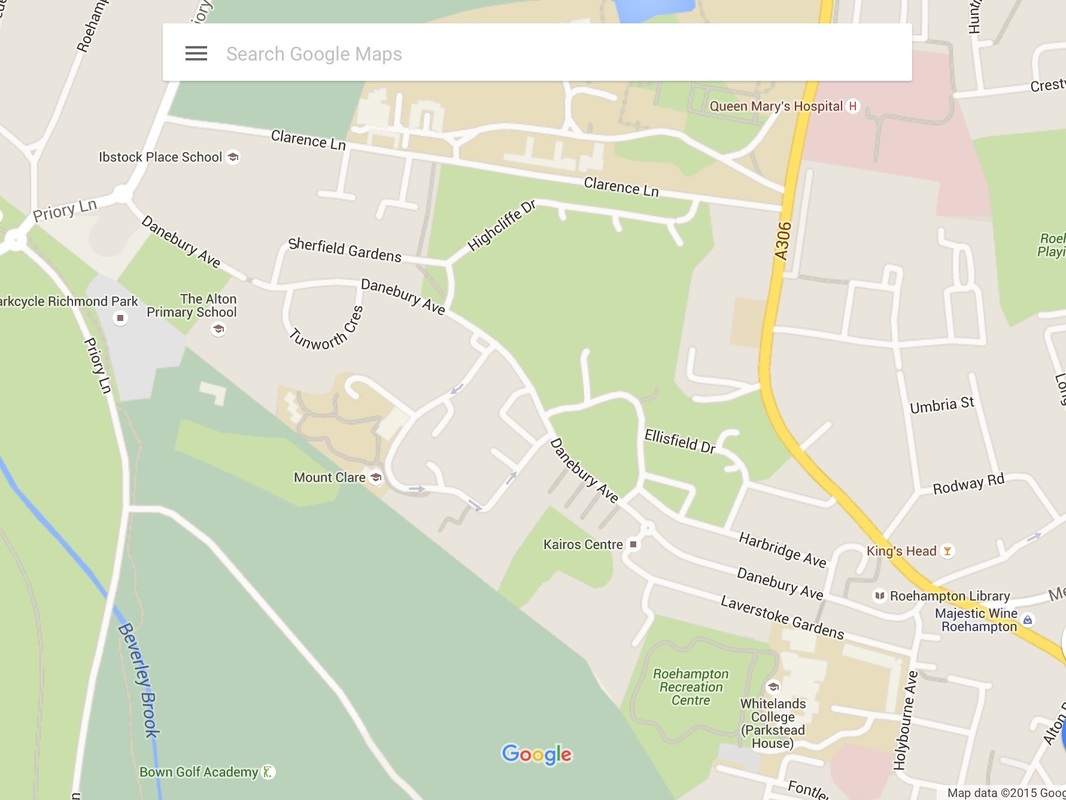

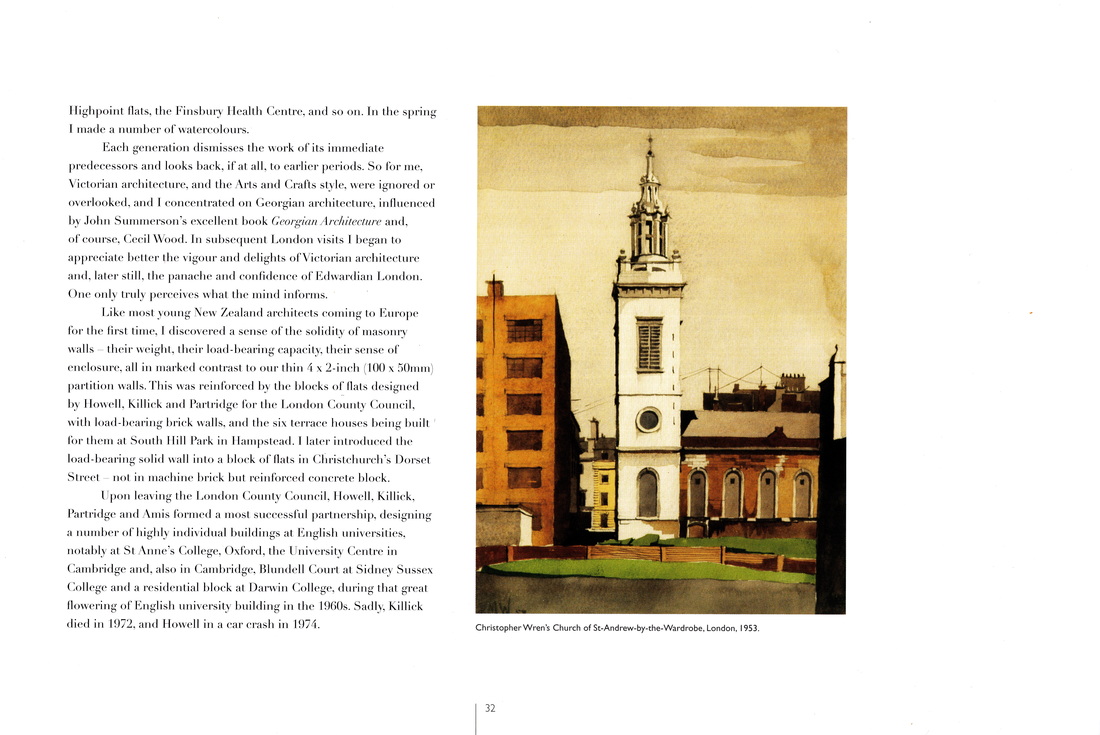

Roehampton had a long history as a summer country retreat for the well to do of London. Popularised in the 17th and 18th centuries, large manor houses were scattered around the royal parkland of Richmond Park and Putney Heath. Parkstead House, built in 1763, had by 1861 become a Jesuit seminary. It, along with others, Downshire House (1770) and Mount Clare (1772) among them, still stand today under the care of the University of Roehampton. Just ten kilometres southwest of Charing Cross, the area now forms part of the London Borough of Wandsworth.

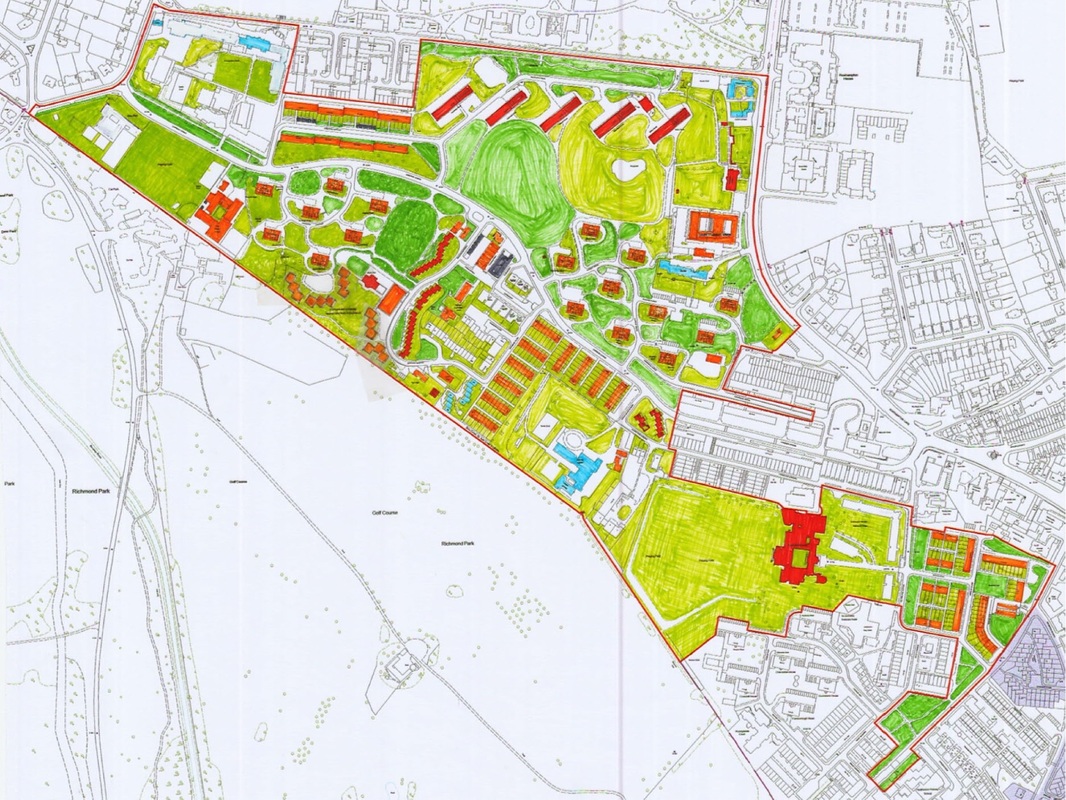

The land for the Alton estates had been acquired after the war, and two competing teams were put to work on the two sides of the grounds. The site encapsulates the arguments within modernism raging at the time: the East follows the Scandinavian “arts and crafts” influence; the West the hardline New Brutalism of Le Corbusier - it was an architectural battleground.

“Alton West [1955-59] represented the triumph of the hards, as the earlier Alton East (1951-54) represented the high point of Swedish empiricism.”[6]

The land for the Alton estates had been acquired after the war, and two competing teams were put to work on the two sides of the grounds. The site encapsulates the arguments within modernism raging at the time: the East follows the Scandinavian “arts and crafts” influence; the West the hardline New Brutalism of Le Corbusier - it was an architectural battleground.

“Alton West [1955-59] represented the triumph of the hards, as the earlier Alton East (1951-54) represented the high point of Swedish empiricism.”[6]

Work on Alton East had started somewhat earlier than that of it’s neighbour. Designed in 1951 and built in 1952-55 under architect-in-charge Rosemary Stjernstedt, assisted by A.W. Cleeve Barr, Oliver Cox and engineers Ove Arup and Partners, the estate consists of a mix of high and low-rise housing, with brightly coloured brickwork exteriors, painted window frames and projecting balconies. The estate was largely completed by 1955.

Both East and West are set in grounds of rolling parkland with the buildings following the natural contours of the land. Alton West mostly occupied the grounds of the late 18th century estates, including gardens laid out by Lancelot “Capability” Brown. The views from the point blocks across to Richmond Park are priceless.

The style of the West however is raw, untreated concrete, with no obvious decoration, and takes it’s cues from Le Corbusier’s La Ville Radieuse - The Radiant City. The estate is made up of seventeen 12-storey point blocks with four flats on each floor, terrace blocks of two and four-storey maisonettes, rows of senior’s cottages, commercial and communal buildings, and, most famously, five eleven-storey slab blocks of two-level flats marching across the Georgian landscape of Downshire Field. The slab blocks in particular drew heavily from Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation, recently completed in south Marseille, (and to which Warren and Weston would visit on their homeward journey in the summer of 1955).

The library and neighbouring Allbrook House were among the last structures completed in 1961.

John Partridge talks about Alton West. Click on picture to play video.

John Partridge talks about Alton West. Click on picture to play video.

The West project team was led by Colin Lucas as architect-in-charge, architects Bill Howell, John Killick, John Partridge, Stan Amis, J.R. Galley and R. Stout, with a staff of draughtsmen, (including Miles Warren) and engineers W.V. Zinn and Partners.

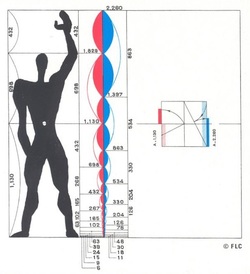

“Stan Amis and I worked on the 12-storey tower blocks. It was my job to organise the plans onto the modular, which was Le Corbusier’s proportional dimension system. Round and round the plan I went, trying to reconcile the maddening dimensions. Even the position of the sink had to be on the modular - to hell with any practical requirements.”[7]

“Stan Amis and I worked on the 12-storey tower blocks. It was my job to organise the plans onto the modular, which was Le Corbusier’s proportional dimension system. Round and round the plan I went, trying to reconcile the maddening dimensions. Even the position of the sink had to be on the modular - to hell with any practical requirements.”[7]

Neither metric nor imperial, maddening it must have been. “Le Modulor” was a system of measurements based on an anthropometric scale of proportions, a modernist version of da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, devised by Le Corbusier to bring a human scale to architectural and mechanical things. Begun in 1943, refined in 1945, and recalculated in 1946, it was based on the measurements of a man 1.83 metres in height, with one arm upstretched. Two vertical scales were then applied: a red series based on the figure’s naval height (1.13 metres in the final version) then segmented according to Phi, and a blue series based on the figure’s total height (double that of the naval, at 2.26 metres in the final version), and segmented in the same way. John Partridge later explained:

“We evolved for this scheme a dimensional system aimed at creating a scale reference for all the buildings in this mixed development. This was our own anglicised form of Le Corbusier’s Modulor based on the Fibonacci series of numbers and related to scales in feet and inches. This dimensional system meant that most proportions became either golden sections or squares, or more complex arrangements of those two basic shapes. Thus we were disciples of Le Corbusier.”[8]

“We evolved for this scheme a dimensional system aimed at creating a scale reference for all the buildings in this mixed development. This was our own anglicised form of Le Corbusier’s Modulor based on the Fibonacci series of numbers and related to scales in feet and inches. This dimensional system meant that most proportions became either golden sections or squares, or more complex arrangements of those two basic shapes. Thus we were disciples of Le Corbusier.”[8]

While the heritage-listed Corbusian slab blocks are the jewels of the estate, the point blocks which occupied Warren are themselves worthy. Flat-roofed, faced with aggregate concrete, and featuring recessed balconies set flush against exterior walls, the perfectly rectangular blocks each contain 44 flats - 4 to a floor, with a central lift lobby and stairwells at either end. Each level consists of two one-bedroom and two two-bedroom flats. Each flat has a separate kitchen, bathroom and toilet, and a small balcony off the living room, and the design ensures that no two living rooms are horizontally adjacent. The cost of constructing the point blocks, seen as more expensive than slab block designs, had originally caused concern for the Finance Committee at the LCC.[9] This resulted in higher rents being charged for these flats, meaning a more middle class resident was targeted, and although this varied the population of the estate more so than in most, the clumping together of the point blocks in two distinct areas still made for a level of economic segregation.

The Alton Estates were as close as Britain ever got to realising the Ville Radieuse - the city in the sky set amid green parkland. They won national and international acclaim,[10] and were named by some the best public housing in the country. In 1966, Francois Truffaut used the estate at the beginning and end of his film “Fahreneit 451”, although in a less than glowing light. Under Thatcher’s controversial Housing Act 1980, residents were given the “Right to Buy” option for their flats, and many did so. For the Conservative Borough of Wandsworth however, it was the end of their interest in social housing. Due perhaps to their visible profile and the high regard in which they were held, the two estates managed to escape the worst of the urban blight and decay which affected many other London council properties in the ’80s and ’90s. Certain buildings were listed by English Heritage in 1998, and since then, various local council plans have been mooted for redeveloping parts of the site. Local residents groups such as Alton Regeneration Watch[11] keep a mindful eye on anything threatening the integrity of the estate. Architects Howell, Killick, Partridge and Amis went on to form a very successful private practice, responsible for a number of fine modernist educational buildings throughout the country.

For Miles Warren though, his turn was up - it was time to return home.

“I left just before Roehampton Lane was built, and first saw the completed development in a copy of the French magazine Aujord’hui.”[12]

“I left just before Roehampton Lane was built, and first saw the completed development in a copy of the French magazine Aujord’hui.”[12]

London and the return home

Time outside of the draughting office was an education for an inquisitive young architectural mind.

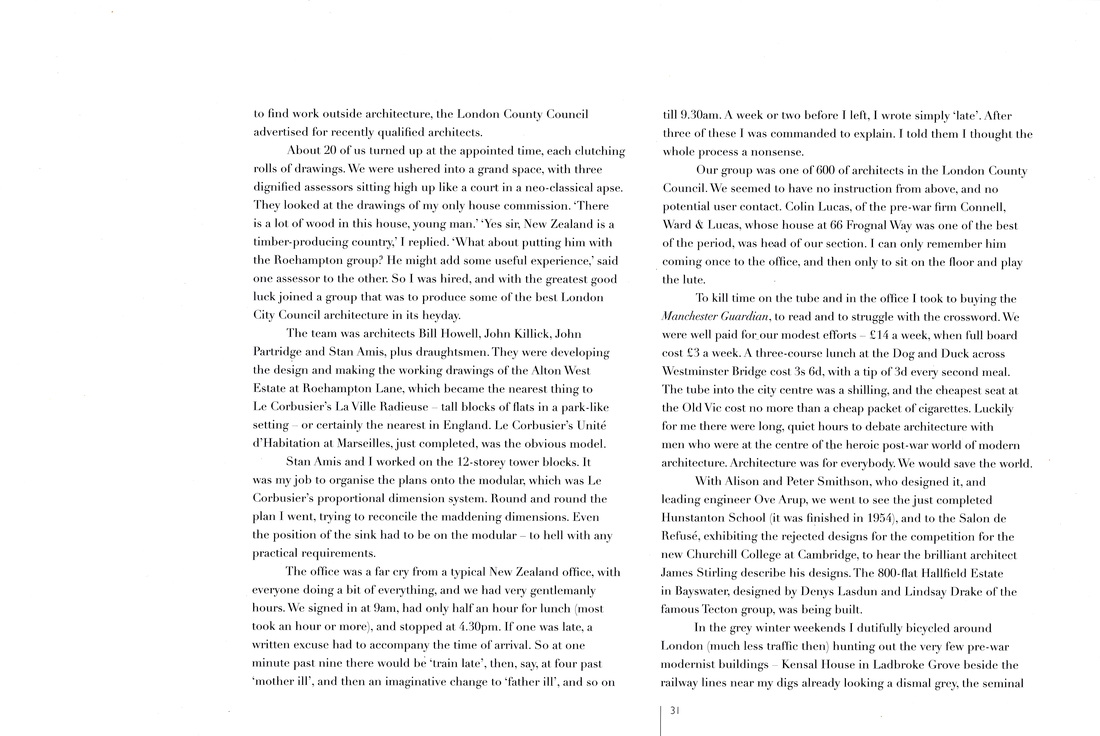

“With Alison and Peter Smithson, who designed it, and leading engineer Ove Arup, we went to see the just completed Hunstanton School (it was finished in 1954), and to the Salon de Refusé, exhibiting the rejected designs for the competition for the new Churchill College at Cambridge, to hear the brilliant architect James Stirling describe his designs. The 800-flat Hallfield Estate in Bayswater, designed by Denys Lasdun and Lindsay Drake of the famous Tecton group, was being built.

In the grey winter weekends I dutifully bicycled around London (much less traffic then) hunting out the very few pre-war modernist buildings - Kensal House in Ladbroke Grove beside the railway lines near my digs already looking a dismal grey, the seminal Highpoint Flats, the Finsbury Health Centre, and so on.”[13]

A further influential visit had been to the South Hill Flats, a group of six terrace houses designed by Howell and Amis being built in Hampstead.

“This flat-roofed, reinforced concrete terrace with its banks of large south-facing windows and balconies not only gave each of the families involved a house of their own but a separate flat to lease. Interior finishes included white painted brick and blockwork with timber. In the Dorset Street Flats, all the ideas would merge with Warren's own particular aesthetic and concepts for modern living."[14]

Time outside of the draughting office was an education for an inquisitive young architectural mind.

“With Alison and Peter Smithson, who designed it, and leading engineer Ove Arup, we went to see the just completed Hunstanton School (it was finished in 1954), and to the Salon de Refusé, exhibiting the rejected designs for the competition for the new Churchill College at Cambridge, to hear the brilliant architect James Stirling describe his designs. The 800-flat Hallfield Estate in Bayswater, designed by Denys Lasdun and Lindsay Drake of the famous Tecton group, was being built.

In the grey winter weekends I dutifully bicycled around London (much less traffic then) hunting out the very few pre-war modernist buildings - Kensal House in Ladbroke Grove beside the railway lines near my digs already looking a dismal grey, the seminal Highpoint Flats, the Finsbury Health Centre, and so on.”[13]

A further influential visit had been to the South Hill Flats, a group of six terrace houses designed by Howell and Amis being built in Hampstead.

“This flat-roofed, reinforced concrete terrace with its banks of large south-facing windows and balconies not only gave each of the families involved a house of their own but a separate flat to lease. Interior finishes included white painted brick and blockwork with timber. In the Dorset Street Flats, all the ideas would merge with Warren's own particular aesthetic and concepts for modern living."[14]

In 1955 though, Warren decided to return home to New Zealand, and in the summer of that year, set off on one last road trip across Europe with his friend Michael Weston. In a Ford Anglia, they drove across France, stopping at Marseille to pay homage to Le Corbusier’s famed Unité d’Habitation, and on to Italy, where began Warren’s love affair with the Eternal City of Rome. Then sailed for home.

But what had the young architect taken away? In his forward to the 2005 retrospective of the Warren and Mahoney practice, he writes:

“European travels and working at the London City Council had introduced me to the substance and weight of masonry walls, the complete opposite of our New Zealand light-weight, thin timber wall tradition. The flats in Dorset Street started our use of load bearing reinforced concrete block, developed with the brilliant engineer Lyall Holmes. The technique and resultant forms were developed via a number of small blocks of flats and reached its peak at 65 Cambridge Terrace and Christchurch College.

The exposed concrete and white painted concrete block contrasted with timber roofs of exposed rafters and boarding, carried on the New Zealand tradition of architects trained and thinking like carpenters, a tradition which culminated in the next generation of architects.”[15]

Barry Dacombe, who joined Warren and Mahoney in 1966, and later became Chairman of the Company (1994-2000), expands on Warren’s forward later in the same volume:

“He was there at the time of the New Brutalism style in architecture and gained an appreciation of the detailing of weighty masonry and precast concrete. This experience, coupled with his earlier New Zealand ‘carpentry’ craft of assembling and connecting elements of buildings, and his already well trained eye for proportion, scale and form, gave rise to a new way of detailing buildings that expressed this ‘connection’ process. It was called ‘negative detailing’ and started a new wave in architecture in New Zealand that was the beginning of what became the ‘Christchurch Style’ of the 1960s…

This technique of detailing and joining materials continued to be developed by the craftsman and his followers, and became the refined and sophisticated aesthetic of Christchurch architecture.”[16]

The Dorset Street Flats were Warren’s opportunity to put all he had learned into practice.

“For me it was the perfect commission - my partners gave me a free hand and I was able to put my theories into practice and stuff the design full of everything I knew, including all my university and London experience.”[17]

It was 1956.

But what had the young architect taken away? In his forward to the 2005 retrospective of the Warren and Mahoney practice, he writes:

“European travels and working at the London City Council had introduced me to the substance and weight of masonry walls, the complete opposite of our New Zealand light-weight, thin timber wall tradition. The flats in Dorset Street started our use of load bearing reinforced concrete block, developed with the brilliant engineer Lyall Holmes. The technique and resultant forms were developed via a number of small blocks of flats and reached its peak at 65 Cambridge Terrace and Christchurch College.

The exposed concrete and white painted concrete block contrasted with timber roofs of exposed rafters and boarding, carried on the New Zealand tradition of architects trained and thinking like carpenters, a tradition which culminated in the next generation of architects.”[15]

Barry Dacombe, who joined Warren and Mahoney in 1966, and later became Chairman of the Company (1994-2000), expands on Warren’s forward later in the same volume:

“He was there at the time of the New Brutalism style in architecture and gained an appreciation of the detailing of weighty masonry and precast concrete. This experience, coupled with his earlier New Zealand ‘carpentry’ craft of assembling and connecting elements of buildings, and his already well trained eye for proportion, scale and form, gave rise to a new way of detailing buildings that expressed this ‘connection’ process. It was called ‘negative detailing’ and started a new wave in architecture in New Zealand that was the beginning of what became the ‘Christchurch Style’ of the 1960s…

This technique of detailing and joining materials continued to be developed by the craftsman and his followers, and became the refined and sophisticated aesthetic of Christchurch architecture.”[16]

The Dorset Street Flats were Warren’s opportunity to put all he had learned into practice.

“For me it was the perfect commission - my partners gave me a free hand and I was able to put my theories into practice and stuff the design full of everything I knew, including all my university and London experience.”[17]

It was 1956.

Notes:

[1] MILES WARREN, “Style in New Zealand Architecture”, New Zealand Architect 3, 1978, p 2 (edited).

[2] MILES WARREN, “An Autobiography”, Canterbury University Press, 2008, p 29.

[3] “An Autobiography”, p 30.

[4] “An Autobiography”, pp 30-31 (edited).

[5] NICHOLAS BULLOCK, “Building the Socialist Dream or Housing the Socialist State? Design versus the Production of Housing in the 1960s”, in “Neo-avant-garde and Postmodern Postwar Architecture in Britain and Beyond”, (ed) Mark Crimson and Claire Zimmerman, The Yale Center for British Art, 2010, pp 328-329.

[6] STEPHEN KITE, “Softs and Hards: Colin St. John Wilson and the Contested Visions of 1950s London” in “Neo-avant-garde and Postmodern Postwar Architecture in Britain and Beyond”, (ed) Mark Crimson and Claire Zimmerman, The Yale Center for British Art, 2010, p 58.

[7] “An Autobiography”, p 31.

[8] Quoted by OLIVER COX in “The Alton Estate: Roehampton After 25 Years”, Housing Review, Sep-Oct 1980, p 171.

[9] NICHOLAS MERTHYR DAY, “The Role of the Architect in Post-War State Housing: A Case Study of the Housing Work of the London County Council 1939-1956”, PhD Thesis for the University of Warwick, 1988, citing the Great London Records Office, Housing Committee, Presented Papers for 23 Sep 1953, “Memo from the Finance Committee”.

[10] BULLOCK, p 329.

[11] www.altonwatch.org.uk

[12] “An Autobiography”, p 33.

[13] “An Autobiography”, pp 31-32.

[14] JESSICA HALLIDAY and CHRISTINE WHYBREW, “Registration Report for a Historic Place: Dorset Street Flats, Christchurch”, Draft 23 December 2009, New Zealand Historic Places Trust, p 8, quoting “Mathew Sturgis 'The Century-Makers: 1956', The Daily Telegraph, 10 January 2004 http://www.telegraph.co.uk/property/3320867/The-century-makers-1956.html

[15] “New Territory: Warren and Mahoney: 50 Years of New Zealand Architecture”, Balasoglou Books, 2005, p 16.

[16] “New Territory”, p 120.

[17] “An Autobiography”, p 43.

[1] MILES WARREN, “Style in New Zealand Architecture”, New Zealand Architect 3, 1978, p 2 (edited).

[2] MILES WARREN, “An Autobiography”, Canterbury University Press, 2008, p 29.

[3] “An Autobiography”, p 30.

[4] “An Autobiography”, pp 30-31 (edited).

[5] NICHOLAS BULLOCK, “Building the Socialist Dream or Housing the Socialist State? Design versus the Production of Housing in the 1960s”, in “Neo-avant-garde and Postmodern Postwar Architecture in Britain and Beyond”, (ed) Mark Crimson and Claire Zimmerman, The Yale Center for British Art, 2010, pp 328-329.

[6] STEPHEN KITE, “Softs and Hards: Colin St. John Wilson and the Contested Visions of 1950s London” in “Neo-avant-garde and Postmodern Postwar Architecture in Britain and Beyond”, (ed) Mark Crimson and Claire Zimmerman, The Yale Center for British Art, 2010, p 58.

[7] “An Autobiography”, p 31.

[8] Quoted by OLIVER COX in “The Alton Estate: Roehampton After 25 Years”, Housing Review, Sep-Oct 1980, p 171.

[9] NICHOLAS MERTHYR DAY, “The Role of the Architect in Post-War State Housing: A Case Study of the Housing Work of the London County Council 1939-1956”, PhD Thesis for the University of Warwick, 1988, citing the Great London Records Office, Housing Committee, Presented Papers for 23 Sep 1953, “Memo from the Finance Committee”.

[10] BULLOCK, p 329.

[11] www.altonwatch.org.uk

[12] “An Autobiography”, p 33.

[13] “An Autobiography”, pp 31-32.

[14] JESSICA HALLIDAY and CHRISTINE WHYBREW, “Registration Report for a Historic Place: Dorset Street Flats, Christchurch”, Draft 23 December 2009, New Zealand Historic Places Trust, p 8, quoting “Mathew Sturgis 'The Century-Makers: 1956', The Daily Telegraph, 10 January 2004 http://www.telegraph.co.uk/property/3320867/The-century-makers-1956.html

[15] “New Territory: Warren and Mahoney: 50 Years of New Zealand Architecture”, Balasoglou Books, 2005, p 16.

[16] “New Territory”, p 120.

[17] “An Autobiography”, p 43.

Thanks to:

Robin Bishop, Steve Fannon, Nieves Carazo and Dermot Cremin of Alton Regeneration Watch, John Horrocks of the Roehampton Forum, and Miriam Howitt, architect, for the guided tour of Alton West on 15 August 2015.

Mark Osborne of www.modernarchitecturelondon.com for his permission to reproduce the floorpans of the Alton West point blocks and South Hill Park flats.

Tom Cordell of www.utopialondon.com for his permission to reproduce the interview video with John Partridge.

Robin Bishop, Steve Fannon, Nieves Carazo and Dermot Cremin of Alton Regeneration Watch, John Horrocks of the Roehampton Forum, and Miriam Howitt, architect, for the guided tour of Alton West on 15 August 2015.

Mark Osborne of www.modernarchitecturelondon.com for his permission to reproduce the floorpans of the Alton West point blocks and South Hill Park flats.

Tom Cordell of www.utopialondon.com for his permission to reproduce the interview video with John Partridge.