|

Don't forget to bookmark our website, www.dorsetstreetflats.com. There's a newly added blog section, and some exciting new content coming soon.

0 Comments

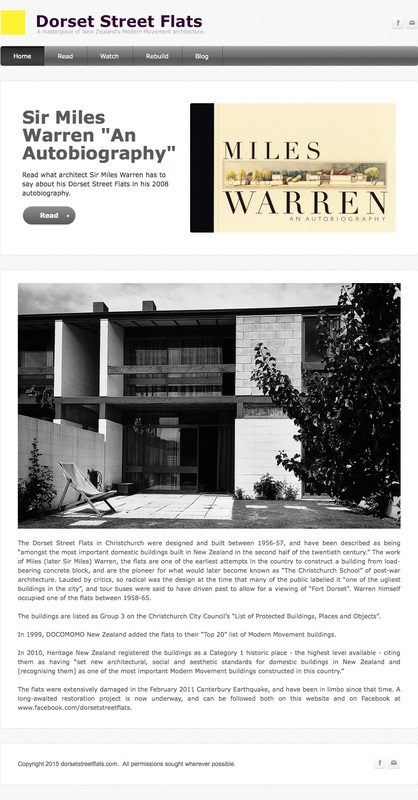

ASSESSMENT CRITERIA FROM HERITAGE NEW ZEALAND: CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE. (b) The association of the place with events, persons, or ideas of importance in New Zealand history: The Flats have special significance as a major early project in Miles Warren's career that allowed full and free articulation of his architectural concerns and the formulation of the influences he acquired while working in Europe. Warren has been recognised nationally and internationally as one of the most important New Zealand architects of the second half of the twentieth century. (e) The community association with, or public esteem for the place: At its construction, 'Fort Dorset' bemused the Christchurch community for its unconventional use of materials and aesthetic approach, and was once reputed to be the ugliest group of buildings in the city. However, the Dorset Street Flats soon became greatly admired in architectural circles, and many prominent New Zealand architects have lived in the Flats. The Flats continue to attract national and international interest as a resolved statement of a new direction in post-war domestic architecture, and the Dorset Street Flats are now well-known and highly regarded among Christchurch residents. http://www.heritage.org.nz/the-list/details/7804  ASSESSMENT CRITERIA FROM HERITAGE NEW ZEALAND: CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE. (a) The extent to which the place reflects important or representative aspects of New Zealand history: The Dorset Street Flats are a response to changing social needs for housing in the post-war period and new requirements for inner-city living among young, single professionals. The Flats marked the emergence of a new kind of residential living in New Zealand: a small-scale group of purpose-designed, modern, modest-sized one-bedroom city flats for minimal living. The influence of this building type on Christchurch domestic architecture is reflected in the repetition of aspects of this design in later projects by Miles Warren and other architects. The Flats possess outstanding significance as an early articulation of Modernism and in the estabiishment of a dwelling type that has become characleristic of Christchurch architecture and highly influential in the development of New Zealand's post-war architecture. http://www.heritage.org.nz/the-list/details/7804 This picture, taken around 1959, by photographer Martin Sydney Barriball (1929-2012) shows the Dorset Street Flats with their original unpainted block walls, (excepting the white stairwell structures), a colour scheme favoured by Warren in the later Carlton Mill Road Flats.

The original is held in the Architectural Centre Collection of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, NZ. PAColl-0811-09-18-02. Used with permission. "Each generation dismisses the work of its immediate predecessors and looks back, if at all, to earlier periods. So for me, Victorian architecture, and the Arts and Crafts style, were ignored or overlooked, and I concentrated on Georgian architecture, influenced by John Summerson’s excellent book 'Georgian Architecture' and, of course, Cecil Wood."

In the light of this week's news concerning neighbouring Bishopscourt, an edited excerpt from Miles Warren's 2008 Autobiography on his time apprenticed to Cecil Wood: "When I told my father I wanted to be an architect he gave a noncommittal humph. Then, sensibly, and unbeknown to me, he called upon all the architects he knew. So, as a 16-year-old, with no formal tutoring in art and no experience in technical drawing, I started as a junior, most junior, draughtsman in Wood’s office at 30 shillings a week, which was 5s more than the going rate. I was, in effect, an articled pupil, paid little but due to receive training from my employer. But I was employed by an architect I now consider to be one of New Zealand’s foremost architects in the period before and after the First World War. Wood set about training his newest recruit. I was given the usual equipment, including an ivory-handled ruling pen, then set-up with a drawing board and told to produce lettering - never, but never, called printing. For an hour each morning I practised evenly spaced vertical lines. Cs were made with two strokes: one up, thickening as it went, and one down, both finishing a little above and below the line. My efforts were pronounced immature, whatever that meant. It seemed tedious and pointless at the time, but it was excellent training in the control of one’s pencil. I still enjoy making good lettering. Beautiful, clear lettering transformed drawings - a craft that will, I suppose, disappear with computer-aided draughting. Next I was given the plans of Wood’s most recent building, his own house, to trace in pen and ink. I drew the elevation of the end gable. Wood asked me whether it would look better with the central window a little higher, wider, narrower, and with the roof pitch steeper or shallower. I drew each variation and was then asked which one I preferred. It was a simple, clear introduction to the delights of proportion, pattern making, window-wall relationships and the two dimensions of the art of architecture. By today’s standards it was a very quiet, slow office - no email, no fax, the telephone rarely rang and few clients called in. In two years the only projects were the [Wellington] cathedral, the sketch plans for a New Zealand Insurance office building in Hereford Street that proceeded no further, sketch plans for an office gateway block for Christ’s College, which also stalled, and one small house. So there was plenty of time for Wood to look over my shoulder as I struggled with ink on linen and the technique and architectural conventions of watercolour. Wood had a superb watercolour technique. His architectural renderings were the best of the time. As a young architect in London he had worked for Robert Weir Schultz, one of the best Edwardian architects, but one who had never had his work exhibited in the architectural section of the Royal Academy. Wood’s fine sketches of two of Schultz’s country houses were accepted. At the end of my first year, Wood told me that I had earned more than he." MILES WARREN, “An Autobiography”, Canterbury University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1-877257-76-6, pp 9-12, 32. |

AuthorKeep up to date by joining our Facebook page. Click on the icon above. Archives

February 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed