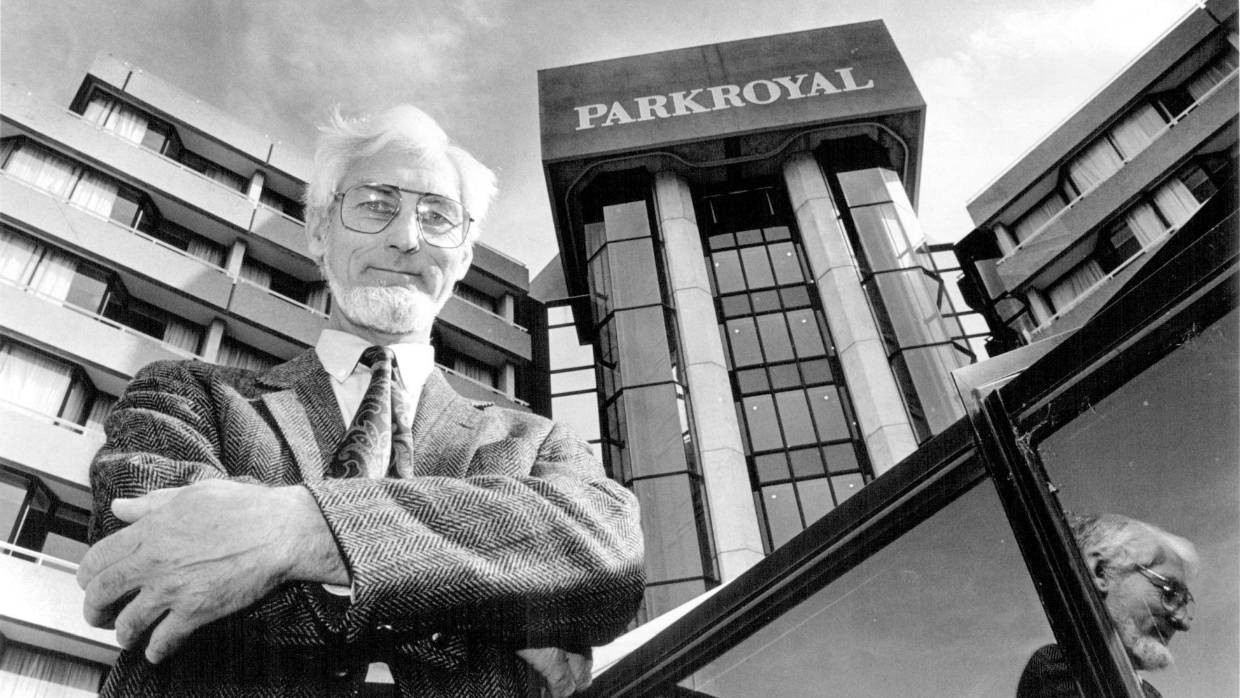

He was making a list of all the buildings from his architecture practice Warren and Mahoney that had survived the Christchurch earthquakes.

It didn't matter that he was in the late stages of terminal pancreatic cancer. He was on a mission and wanted to see for himself which of his buildings were still standing.

And he had good reason to be proud. Maurice Mahoney came from a working class background in east London, but went on to be a driving force behind a distinctive form of modernist New Zealand architecture.

Mahoney was born in the poor east London neighbourhood of Plaistow in 1929. His family moved to New Zealand in 1939 when he was 10.

Their passenger ship was one of the last to leave Europe because World War Two had been declared just a few weeks earlier. The ships moved in a convoy across the Atlantic under blackout conditions. The ship behind theirs was sunk by a German submarine, his daughter says.

The family settled in Sydenham, Christchurch. His father found work as an electrical engineer at a printing company.

He was interested in architecture from an early age, but his family could not afford to send him to university, Jane Mahoney said.

His family moved to Opawa in the 1950s. He designed a house for them on Opawa Rd when he was only 23. He fell in love with the girl next door, marrying Margaret in 1960. The two would remain together until his death, raising four children – Sarah, Jane, Nigel and Emma.

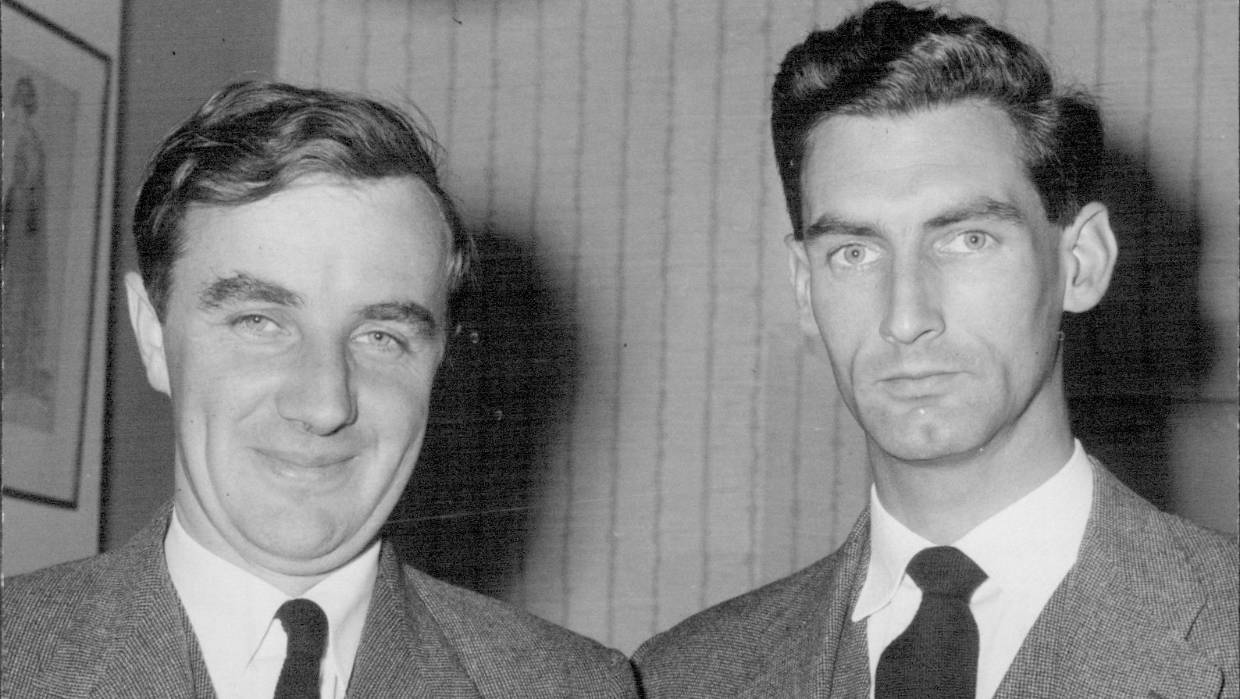

He met Miles Warren when he was 16. They would go on to form a partnership that would define their professional lives, forming the company Warren and Mahoney in 1958 when they were both in their twenties.

His daughter said the partnership between Warren and Mahoney worked because they were such different characters.

"They were almost chalk and cheese," she said.

Warren said the partnership worked "because each of us supplied what the other lacked."

Architectural historian Jessica Halliday said Mahoney was a "giant of New Zealand architecture" who "led the post-war revolution in modernism".

"He was very tall and proper. You were very aware of this lean, tall and upright figure that was quiet and solid and modest.

"The same was true about his work. He did a lot of the solid work."

"He was a craftsmen. He understood the craft of architecture. He understood how buildings came together and got great pleasure from doing so.

"Whenever a drawing left his office it was ready and correct and accurate. It never had to come back."

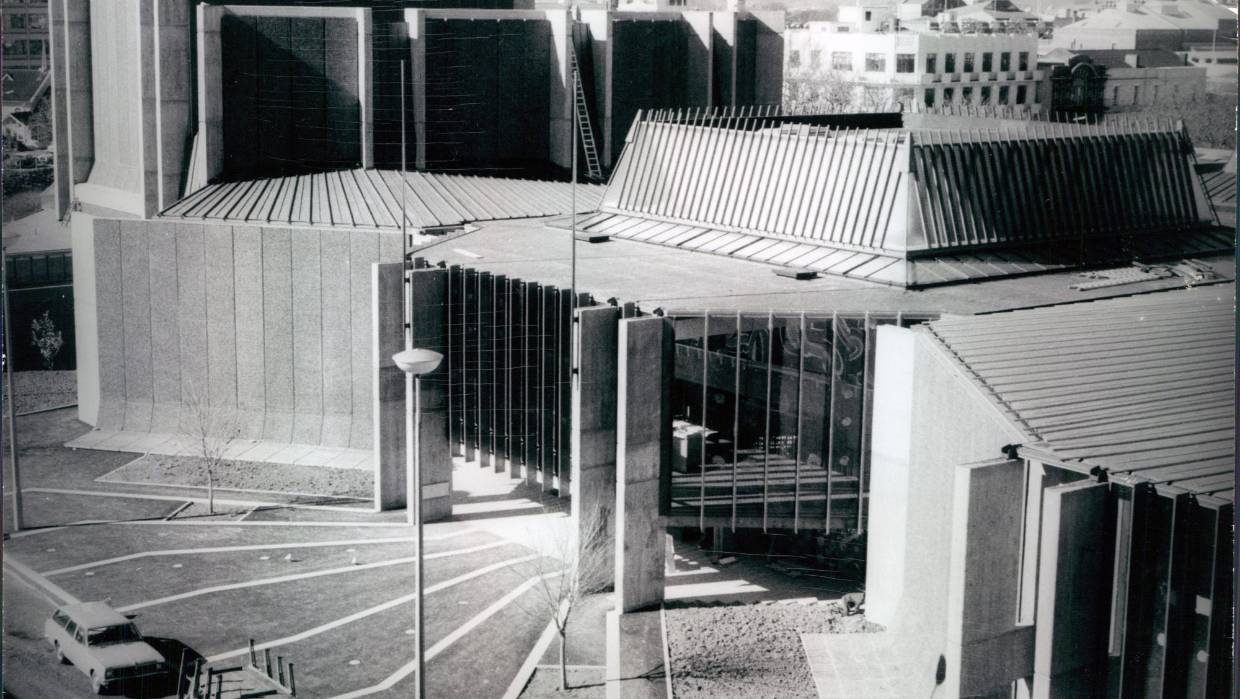

The Town Hall was one of Mahoney's proudest achievements. His daughter said he was sad not to be there for the reopening of the refurbished building in March next year.

"The original opening of the Town Hall was a huge thrill for his parents. It was a really proud and emotional time. We are all gutted that he will not be be there for the reopening next year."

But the Town Hall is a rare survivor of Warren and Mahoney's prolific reign in Christchurch. Many of their buildings were demolished after the 2011 earthquakes.

"He found it very frustrating that a huge percentage of his buildings were pulled down when he believed they could have been repaired," Jane Mahoney said.

But Warren remembers "the pleasure of designing and making buildings together" with Mahoney and pictures him "quietly working away making superb drawings."

He said Mahoney's death was "sad, but inevitable".

"We had a very good run. We knew when to stop."

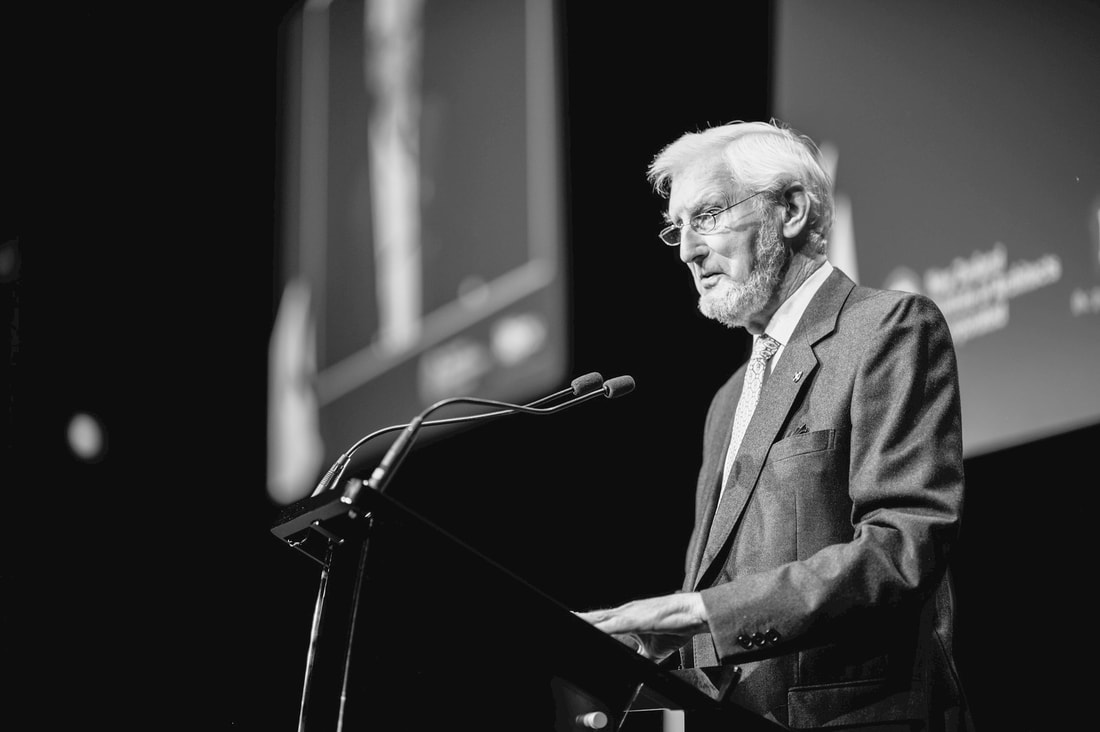

In his final months, Mahoney turned that meticulous attention to detail to his own funeral arrangements. He designed the displays for the ceremony and left detailed notes for speakers at the funeral, Jane Mahoney said.

"He wrote instructions to sit on the lectern. It instructed people to speak directly into the microphone."

"He was a details man."

CHARLIE GATES, stuff.co.nz, 2 November 2018.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed