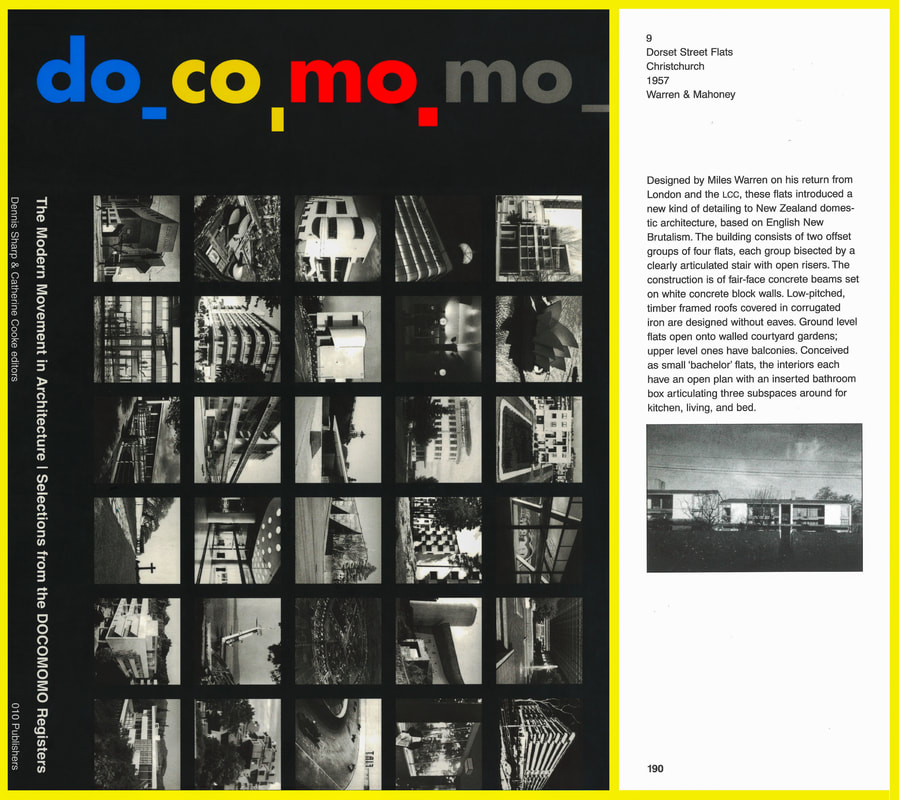

In 1999, DOCOMOMO New Zealand compiled a ’top 20′ list of buildings, sites and neighbourhoods for publication in Dennis Sharp and Catherine Cooke (eds), The Modern Movement in Architecture: Selections from the DOCOMOMO Registers (010 Publishers, Rotterdam, 2000). Dorset Street Flats is included amongst the twenty local buildings listed.

|

DOCOMOMO is the international working party for the DOcumentation and COnservation of buildings, sites and neighbourhoods of the MOdern MOvement. Initiated by the University of Eindhoven, the Netherlands, in 1988, it is the most significant non-governmental organisation of experts devoted to the history, preservation and reassessment of modern architecture.

In 1999, DOCOMOMO New Zealand compiled a ’top 20′ list of buildings, sites and neighbourhoods for publication in Dennis Sharp and Catherine Cooke (eds), The Modern Movement in Architecture: Selections from the DOCOMOMO Registers (010 Publishers, Rotterdam, 2000). Dorset Street Flats is included amongst the twenty local buildings listed.

0 Comments

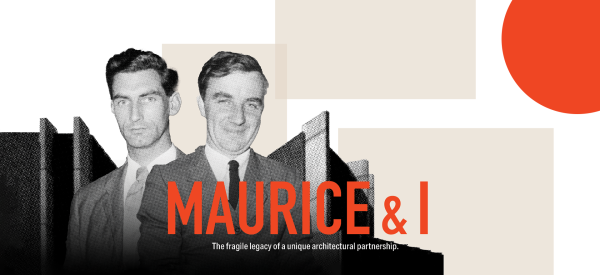

Filming this week at Dorset Street Flats for the new documentary film “Maurice & I”, due in theatres later this year.

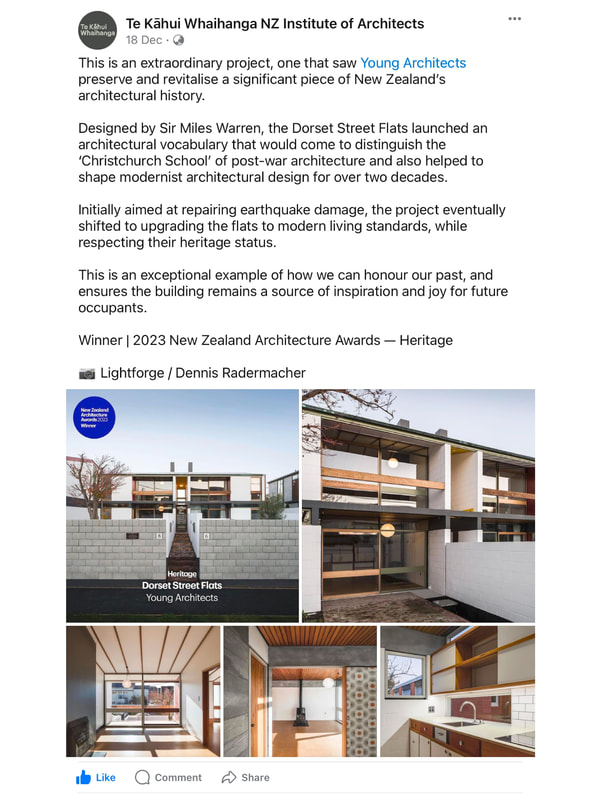

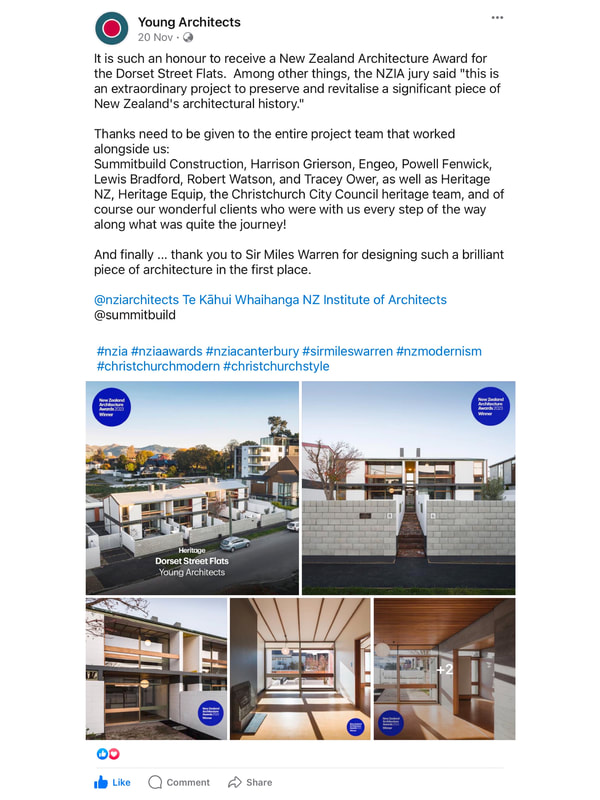

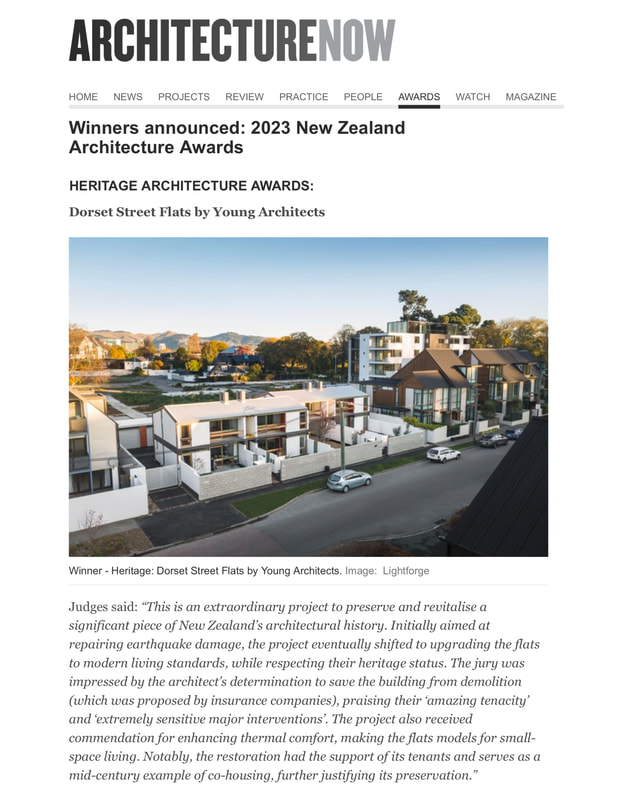

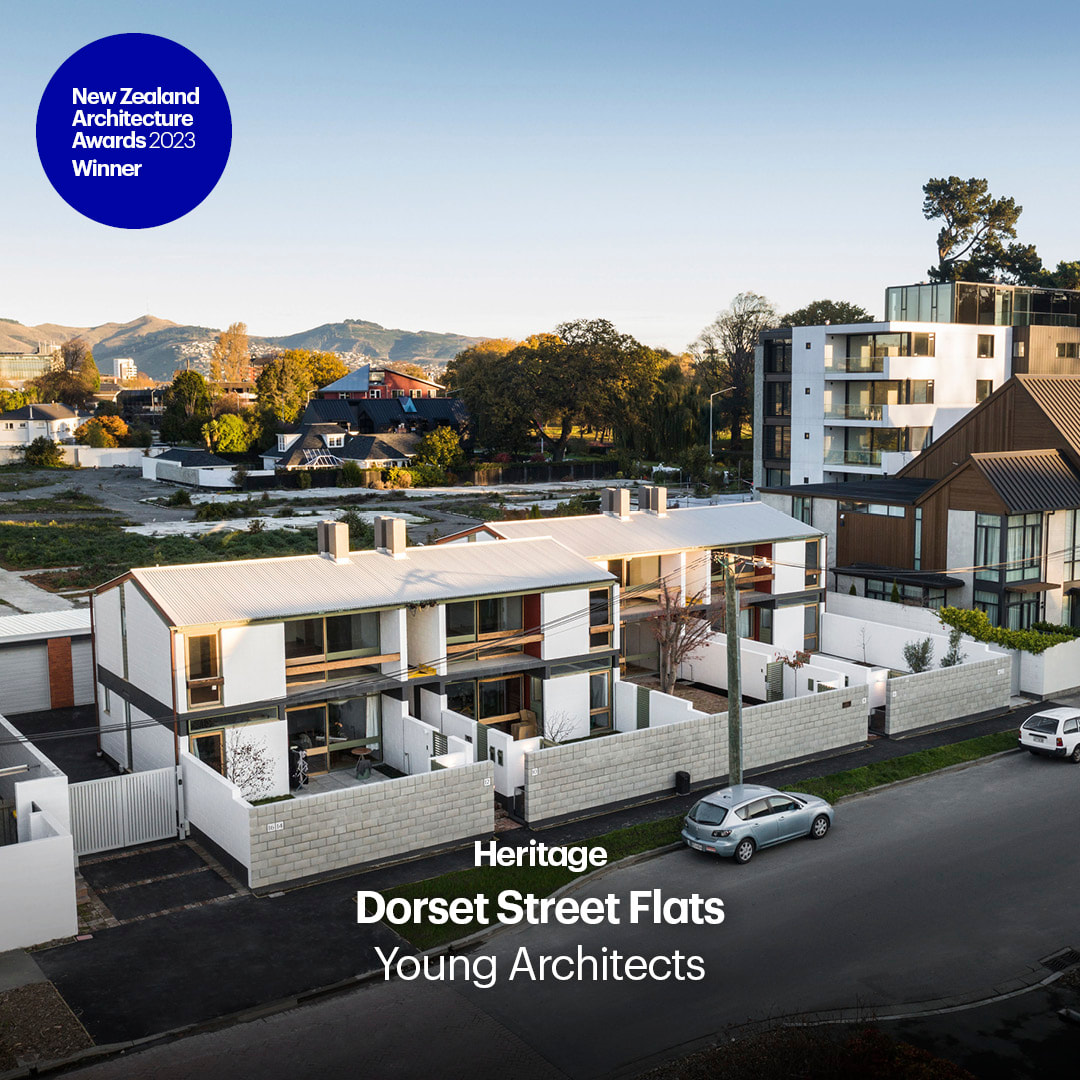

Judges said: "This is an extraordinary project to preserve and revitalise a significant piece of New Zealand's architectural history. Initially aimed at repairing earthquake damage, the project eventually shifted to upgrading the flats to modern living standards, while respecting their heritage status. The jury was impressed by the architect's determination to save the building from demolition (which was proposed by insurance companies), praising their 'amazing tenacity' and extremely sensitive major interventions'. The project also received commendation for enhancing thermal comfort, making the flats models for small-space living. Notably, the restoration had the support of its tenants and serves as a mid-century example of co-housing, further justifying its preservation."

Thank you to Te Kāhui Whaihanga NZ Institute of Architects for this wonderful recognition at tonight’s New Zealand Architecture Awards, and congratulations to Young Architects.

Winners of the NZIA Awards 2023 will be announced on Thursday 16 November.

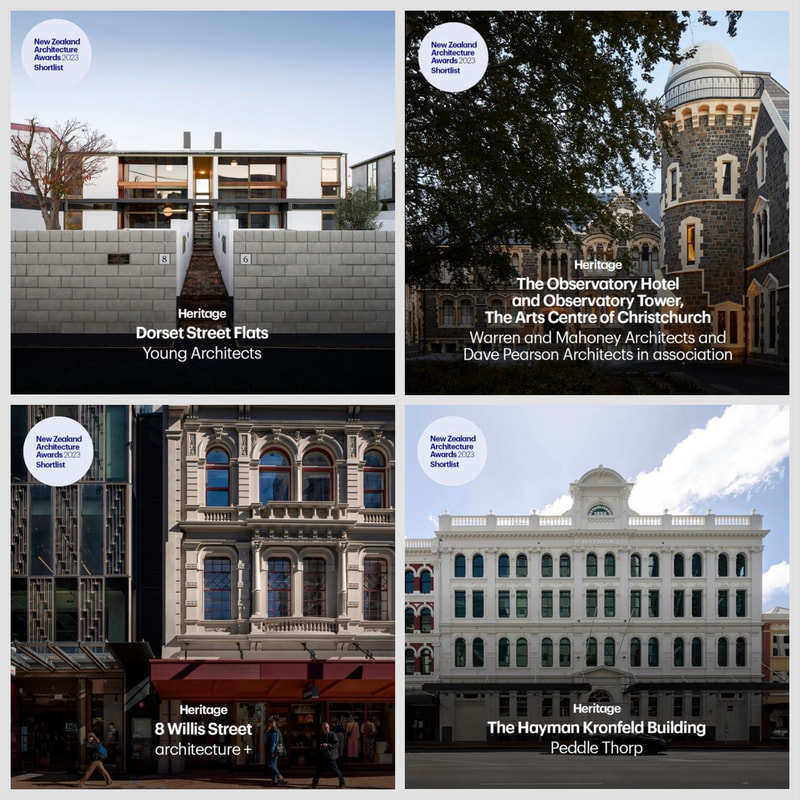

These are the shortlisted entries in the Heritage category. "Maurice & I" is a feature-length documentary celebrating Sir Miles Warren and Maurice Mahoney’s hugely influential architectural partnership, and their legacy that was all but lost in the devastating Christchurch earthquakes.

There are four weeks left to donate to this wonderful venture. Please consider supporting. https://boosted.org.nz/projects/maurice-and-i |

AuthorKeep up to date by joining our Facebook page. Click on the icon above. Archives

February 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed